Around the year 1600 B.C., the Hyksos came to power for a short period only to be removed by Ahmose (ruled 1570-1546 B.C.), the son of the last ruler of the Seventeenth Dynasty, who also unified the country. During the New Kingdom, Egypt reached the peak of its power, wealth, and territory. The government was reorganized into a military state with an administration centralized in the hands of the pharaoh and his chief minister. Through the intensive military campaigns of Pharaoh Thutmose III (1490-1436 B.C.), Palestine, Syria, and the northern Euphrates area in Mesopotamia were brought within the New Kingdom. This territorial expansion involved Egypt in a complicated system of diplomacy, alliances, and treaties. After Thutmose III established the empire, succeeding pharaohs frequently engaged in warfare to defend the state against the pressures of Libyans from the west, Nubians and Ethiopians from the south, Hittites from the east, and Philistines (sea people) from the Aegean-Mediterranean region of the north.

Toward the end of the Twentieth Dynasty, Egyptian power declined at home and abroad. Egypt was once more separated into its natural divisions of Upper Egypt and Lower Egypt. The pharaoh now ruled from his residence-city in the north, and Memphis remained the hallowed capital where the pharaoh was crowned and his jubilees celebrated. Upper Egypt was governed from Thebes.

During the Twenty-first Dynasty, Egyptian control in Nubia and Ethiopia vanished. The pharaohs of the Twenty-second and Twenty -third dynasties were mostly Libyans. Those of the brief Twenty-fourth Dynasty were Egyptians of the Nile Delta, and those of the Twenty-fifth were Nubians and Ethiopians. This dynasty's ventures into Palestine brought about an Assyrian intervention, resulting in the rejection of the Ethiopians and the reestablishment by the Assyrians of Egyptian rulers at Sais (Sa al Hajar), about eighty kilometers southeast of Alexandria on the Rosetta branch of the Nile.

Much of wealth in art and architecture of the civilization of the New Kingdom remains. The treasures from the tomb of Tutankhamen (1347-1337 B.C.) show the refined art of the period and the skills of the artisans of the day.

One of the innovations of the period was the construction of rock tombs for the pharaohs and the elite. Around 1500 B.C., Pharaoh Amenophis I abandoned the pyramid in favor of a rock-hewn tomb in the crags of western Thebes (Luxor). His example was followed by his successors, who for the next four centuries cut their tombs in the Valley of the Kings and built their mortuary temples on the plain below. Other wadis or river valleys were subsequently used for the tombs of queens and princes.

Another New Kingdom innovation was temple building, which began with Queen Hatshepsut. She was particularly devoted to the worship of the god Amun, whose cult was centered at Thebes. She built a temple dedicated to him and to her own funerary cult at Dayr al Bahri in western Thebes.

One of the greatest temples still standing is that of Pharaoh Amenophis III at Thebes. With Amenophis III, statuary on an enormous scale makes its appearance. The most notable is the pair of colossi, the so-called Colossi of Memnon, which still dominate the Theban plain before the vanished portal of his funerary temple.

Ramesses II was the most vigorous builder. Nearly half the temples remaining in Egypt date from his reign. Some of his constructions include his mortuary temple at Thebes, popularly known as the Ramesseum; the huge hypostyle hall at Karnak, the rock-hewn temple at Abu Simbel (Abu Sunbul); and his new capital city of Pi Ramesses.

The Cult of the Sun God and Akhenaten's Monotheism

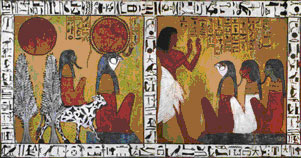

During the New Kingdom, the cult of the sun god Ra became increasingly important until it evolved into the monotheism of Pharaoh Akhenaten (Amenhotep IV, 1364-1347 B.C.). According to the cult, Ra created himself from a primeval mound in the shape of a pyramid and then created all other gods. Ra, or Atne, the Great Disc, was not only the sun god, he was also the universe, and illuminated the world of the living and the dead.

Akhenaten made Aten the supreme state god, symbolized as a rayed disk with each sunbeam ending in a ministering hand. Other gods were abolished, their images smashed, their temples abandoned, and their revenues impounded. The plural word for god was suppressed. Sometime in the fifth or sixth year of his reign, Akhenaten moved his capital to a new city called Akhetaten (Tell al-Amarna). At that time, the pharaoh, previously known as Amenhotep IV, adopted the name Akhenaten. His wife, Queen Nefertiti, shared his beliefs.

Akhenaten's religious ideas did not survive his death. His ideas were abandoned in part because of the economic collapse that ensued at the end of his reign. To restore the morale of the nation, Akhenaten's successor, Tutankhamen, appeased the offended gods. Temples were cleaned and repaired, new images made, priests appointed, and endowments restored. Akhenaten's new city was abandoned.