Modern Luxor is a populous town on the right bank of the River Nile, where ancient Thebes, the city described by Homer as ‘Thebes of the hundred gates', once stood.

The name Luxor comes from the Arabic word el-Uqsur, the plural of el-Qasr, meaning encampment or fortification, with reference to the two military camps built there in Roman times.

Thebes, which the Ancient Egyptians called Waset, extended over the area between modern Karnak and Luxor. In this vast city (at its height it had more than are million inhabitants), at one time capital of an empire that extended from the Euphrates to Upper Nubia, the god Amun was worshipped, and the heart of the Amun cult lay in the great temple of Karnak.

Once a year, on the occasion of the Festival of Opet, in the second and third month of the flood season, a solemn procession would transport the sacred barque of the god from the temple of Karnak to the temple of Luxor, called Ipet-resit, or ‘Private Chambers to the South (of Amun)’.

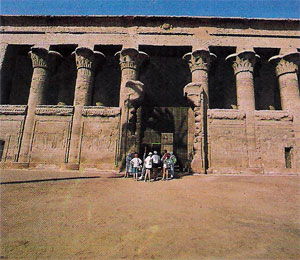

The temple of Luxor, some 260 m (850 ft) long today, was built by Amenophis III on the foundations of a previous religious structure, dating from the time of Queen Hatshepsut.

The queen had also ordered the construction of six kiosks, at the stopping points of the sacred barque of Amun, along the original Eighteenth-Dynasty dromos, the sacred avenue that connected the temple of Luxor with the temple of Karnak.

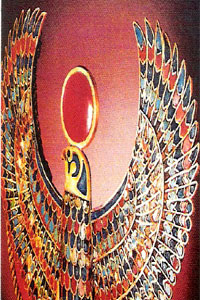

From the Eighteenth Dynasty on, the effigies of the sacred barges of Amun, Mut and Khonsu were sailed to the temple of Luxor along the course of the Nile. At the Festival of Opet, Amun of Karnak paid a visit to Amun of Luxor, also known as Amun-em-ipet, meaning ‘Amun-Who-Is-In-His-Harem’, revitalizing the Amun of Luxor.

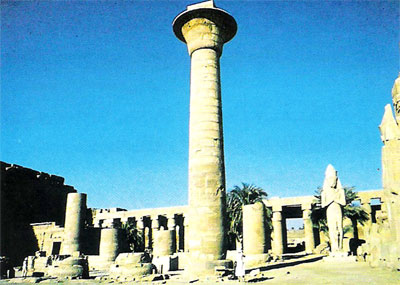

One of the glories of the temple of Luxor is a majestic colonnade dating to the reign of Amenophis III, with 14 columns with papyrus-shaped capitals standing 18 m (60 ft) tall (and almost 10 m (33 ft) in circumference).

The colonnade is enclosed on both sides by a masonry curtain wall, with relieves depicting various phases of the Festival of Opet, completed and decorated during the reigns of Tutankhamun and Horemheb.

A magnificent courtyard followed, lined with a double row of columns, and bordered to the south by the hypostyle hall. From here, the visitor passes on to the inner section of the temple where there is a series of four antechambers and ancillary rooms, and the sanctuary of the sacred barque, situated in the innermost room. The chapel was rebuilt by Alexander the Great.

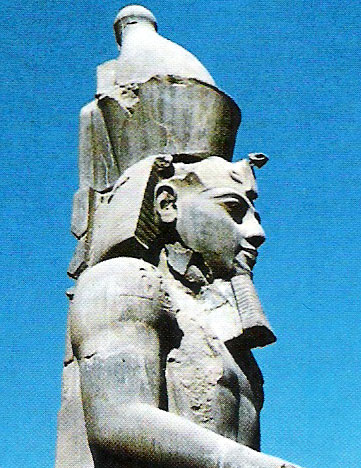

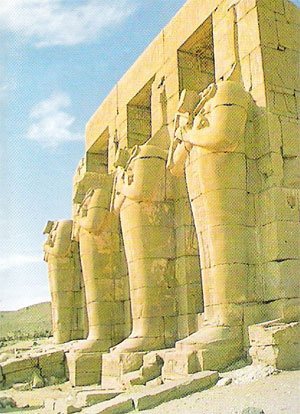

The temple was enlarged by Ramesses II, who built the first pylon, decorated with relives depicting the battle of Qadesh in Syria (1274 BC), the first courtyard and, on the interior of the temple, a triple sanctuary for the barges of Amun, Mut and Khonsu – the Theban triad.

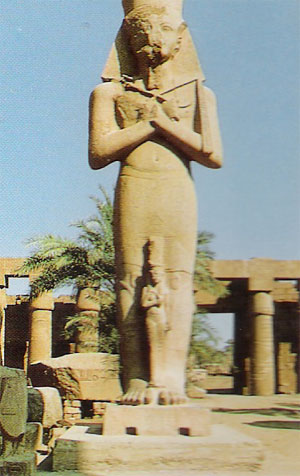

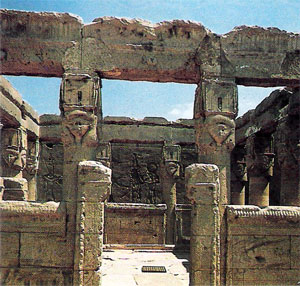

The courtyard of Ramesses II, surrounded by a peristyle of 74 papyrus columns arranged in a double row and adorned with 16 statues of the pharaoh, incorporates a three-part chapel on the northern side, also dedicated to the Theban triad and dating to Hatshepsut’s reign; on the eastern side of the courtyard a Byzantine church was built in the sixth century AD, and on top of that, during the reign of the Ayyubid sultans (thirteenth century AD), the mosque of Abu El-Haggag was built, which is still used today.

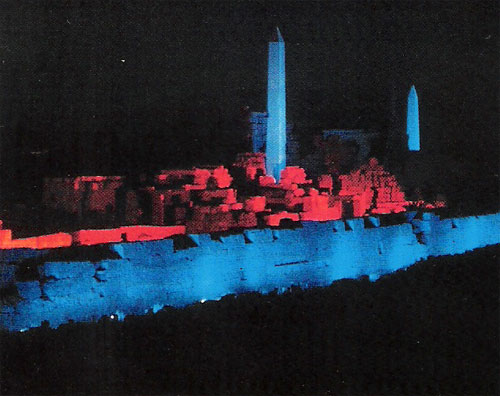

Also dating to the reign of Ramesses II are two large obelisks that once stood before the first pylon (a word derived from the Greek meaning ‘gateway’) and which were given to France by the ruler of Egypt, Mohammad Ali, in 1819.

The western obelisk, more than 21 m (70 ft) tall and weighing 210 tons, was removed by the French in 1836 and erected in Paris in the Place de la Concorde. All claims to ownership over the second obelisk, which remained in its position in Egypt, were renounced by France in 1980.

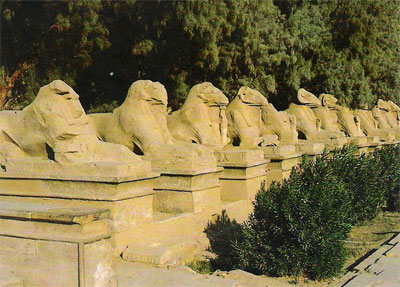

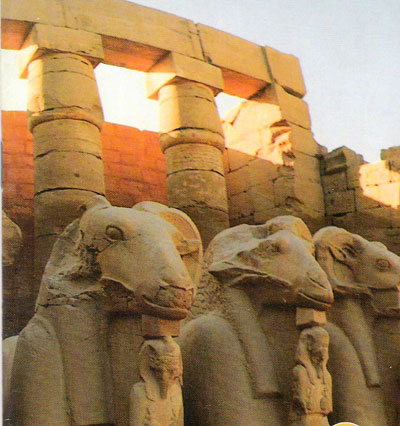

and the avenue of sphinxes that connected the temples of Luxor and Karnak

The ceremonies that took place in the temple of Luxor were of great importance and their religious symbolism was complex. During the Festival of Opet, the feast of the royal jubilee, the divine rebirth of the pharaoh, son of Amun, was celebrated, reaffirming in this way his power.

In the dim light of the ‘hall of divine birth’, Amun, who on this occasion took the form of the pharaoh, would meet the queen. Thoth, the ibis-headed god would announce to her an imminent birth.

Amun would then order Khnum, the ‘Divine Potter’, to shape a baby boy on his potter’s wheel, and his ka, or ‘spirit double’, which would represent the child’s divine and immortal spirit. The queen, assisted by Hathor, Isis and Nephthys, would give birth to the divine son, offspring of pharaoh and gods, recognized by his father Amun.

To Amun, the divine son would make offerings of incense and fresh bowers, receiving in exchange his divine nature, his youth and the promise of long life. He would then be crowned as the legitimate sovereign of the Two Lands. The pharaoh, thus regenerated and reconfirmed in his royal position, could ensure the prosperity of his people for another year.

The temple of Luxor also served as a shrine for the worship of the divine and immortal portion of the pharaoh, the royal ka, symbol of legitimacy of the pharaoh’s power, which was universal and not restricted to any individual pharaoh.

This concept lasted for over seventeen centuries, which explains why Alexander the Great – whose legitimacy as the sovereign of Egypt depended on his being recognized as the son of Amun – chose to rebuild the sanctuary of the god’s Barque.

According to Theban cosmogony, the temple of Luxor was also a recreation of the temple of Heliopolis, the site of collective name for the eight primordial deities, who were engendered by the creator of the earth, the serpent Irta, also known as Kematef, who in turn created the world.

According to myth, Kematef and the Ogdoad, once their mission was accomplished, were buried in a mythical tomb at Medinet Habu where, throughout the New Kingdom, Amun of Luxor would pay a visit every ten days in the ‘Feast of the Tenth Day’.

During the reign of Ramesses II, the procession did not enter the temple through the main entrance of the first courtyard, but through the western gate, overlooking the Nile, the eastern gate being reserved for the populace at large. The main entrance to the temple was used during the annual festival of Amun-Min-Kematef, which celebrated Amun in his capacity as the god of fertility.

During the era of Nectanebo I the dorms linking Luxor to Karnak was adorned with hundreds of human-headed sphinxes, still visible in part. Under Roman rule, specifically during the reign of Emperor Diocletian, around AD 300, the southernmost part of the temple was dedicated to the emperor cult and the temple itself was incorporated into the castrum of the Roman garrison stationed in Luxor.

Excavations in the temple area, almost buried by sand and by houses of the residents of the village of Luxor, were begun in 1885 by Gaston Maspero, who restored the complex to its current state.

In terms of purity of structural design and the elegance of its columns, the temple is one of the most remarkable architectural achievements of the New kingdom.

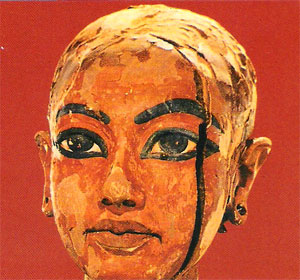

One of the most important finds of recent years was made here, in the courtyard of Amenophis III. A cache of magnificent statues was found, of which the finest, of red quartzite, depicted the pharaoh himself.