Places of the Semi Desert

- Rasafeh

- Qasr al-Hir al-Gharbi

- Qasr al-Hir al-Sharqi

- Raqqa

- Al-Thawra (Tabaqa)

- Deir al-Zor

- Halabiya and Zalabiya

- Al-Hasakeh

Palmyra

Syria has always been a center where East an West meet with their varied civilization. It is no wonder that Syria is the cradle of civilization, which flourished throughout history. Monuments, the most important archaeological sites, impregnable castles, citadels and dead cities narrate the glorious history of ancient nations.

The basaltic and the limestone ruins tell about a marvelous architectural art. The Corinthian columns, the khans spread all over the Silk Road, the castles still towering from the Medieval ages, the mosques and palaces are the witnesses of a great rich history.

To know Syria is to have knowledge of a legendary world. Palmyra, for example, is like a pearl in the heart of the desert, Palmyra, rising from the sands, is one of the most graceful and splendid ancient sites in the East, for the glory and the greatness are still evident and fully years after its construction by the Arab Queen Zenobia. It remains one of most famous capitals of the ancient world.

Palmyra is separated by some one hundred kilometers of steppe from the lush valley of the Orontes, to the west. There are more than two hundred kilometers of desert to the cross before you reach the fertile banks of the Euphrates, to the east. To Both north and south there is nothing but sand and stone. But here at Palmyra a last fold of the Anti- Lebanon forms a kind of basin on the edge of which a spring rises out of a long underground channel whose depth has never been measured. This spring is called Afqa (or Ephka) in inscriptions, an Aramaic word meaning " way out'. Its clear blue, slightly sulphurous waters are said to have medicinal properties; they have fed an oasis here with olives and date- palms and cotton and cereals. For generation this oasis was known as Tadmor.

Stopping-place for caravans taking the short route from the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean, as well as for those taking the silk Route and crossing the Tigris near Seleucis in Babylon.

Tadmor is mentioned on tablets in Cappadocia This remarkable site in the center of the Syrian desert became a necessary dating from the 19th century B.C. From the end of the second millennium Aramaic was the language spoken there, this language persisted until the Byzantine period. Its distinctive written script was respected; later on there were few Greek inscriptions, still fewer Latin ones; Arabic script was very mud, influenced by Palmyrene.

The population consisted - from very early times, half of people of Aramean origin and half of Arab nomads of Nabatean extraction. But it was from the 1st century B.C., when the Romans invaded Syria, that Tadmor (city of dates) now Palmyra (city of palm-trees), took full advantage of her geographical isolation, which gave her some protection against military coups, and her economic opportunity as a staging post between the Orient and the Mediterranean world. Both ships and pack-camels -are to be found sculpted on the facades of her buildings. For four hundred years the city enjoyed uninterrupted prosperity. At the center of the caravan traffic, Palmyra levied heavy taxes on goods in transit.

A desert fortress, she hired out her famous camel troops to the Roman armies. Jealous of her independence she negotiated skillfully with her powerful neighbors, the Romans and the Persians whose expansionist policies were not the least of their faults. In 129 the Emperor Hadrian visited the city. Breaking with his predecessorsi dreams of hegemony he abandoned the Euphrates line and recognized Palmyra as a "Free City", only too pleased to put a buffer-state between the Persians and his Legions. In recognition the city adopted the name of Adriana Palmyra for a time. The main temples were built or enlarged during this period; the agora was made; the residential quarters grew up on both sides of the great colonnaded central avenues.

At the end of the first century, under the Emperor Severus, of African and Syrian origins, Palmyra enjoyed new favors. Moreover, her ancient rival Petra (in present-day Jordan) had disappeared from the scene. In 217 the Emperor Caracalla proclaimed Palmyra a "Roman colony"- a popular move amongst the merchants of the city for it freed them from taxes.

Spices, perfumes, ivory and silks from the East, glassware statues, and objects diart from Phoenicia, all passed through Palmyra. The traffic was organized by the Palmyrians; some of them even owned ships, sailing the Indian Ocean.

Luxury came to Palmyra. Contemporary sculpture depict a wealthy bourgeoisie, believed and splendidly dressed. Magistrates, merchants, citizens whom the city wished to honor, had their statues erected inscribed, on consoles along the innumerable columns that lined the streets. The grand colonnade was extended eastwards and, at the same time another was built, at an angle to it, leading to the Temple of Bel. In the valley of the Tombs, to the east of the city, the "houses of the dead", veritable underground palaces, were decorated with particularly fine sculpture and frescoes.

The whole city reflected activity and great prosperity but this in no way hampered cultural development nor did it restrict innovation in thought. Alongside the traditional worship of Bel, a kind of Babylonian equivalent of Zeus, and his two acolytes RarhibUI (the sun) and AglibUI (the moon), and that of Baalshamain, "Master of the Heavens", a tendency to monotheism very soon appeared - illustrated by dedications "to the one, single, merciful god", "to him whose name is ever blessed", etc. Christianity was already prevaleni before the year 300, since a Palmyrene bishop played .a leading role at the Nicene Council .

At the end of the first century, under the Emperor Severus, of African and Syrian origins, Palmyra enjoyed new favors. Moreover, her ancient rival Petra (in present-day Jordan) had disappeared from the scene. In 217 the Emperor Caracalla proclaimed Palmyra a "Roman colony"- a popular move amongst the merchants of the city for it freed them from taxes.

Spices, perfumes, ivory and silks from the East, glassware statues, and objects diart from Phoenicia, all passed through Palmyra. The traffic was organized by the Palmyrians; some of them even owned ships, sailing the Indian Ocean.

Luxury came to Palmyra. Contemporary sculpture depict a wealthy bourgeoisie, believed and splendidly dressed. Magistrates, merchants, citizens whom the city wished to honor, had their statues erected inscribed, on consoles along the innumerable columns that lined the streets. The grand colonnade was extended eastwards and, at the same time another was built, at an angle to it, leading to the Temple of Bel. In the valley of the Tombs, to the east of the city, the "houses of the dead", veritable underground palaces, were decorated with particularly fine sculpture and frescoes.

The whole city reflected activity and great prosperity but this in no way hampered cultural development nor did it restrict innovation in thought. Alongside the traditional worship of Bel, a kind of Babylonian equivalent of Zeus, and his two acolytes RarhibUI (the sun) and AglibUI (the moon), and that of Baalshamain, "Master of the Heavens", a tendency to monotheism very soon appeared - illustrated by dedications "to the one, single, merciful god", "to him whose name is ever blessed", etc. Christianity was already prevaleni before the year 300, since a Palmyrene bishop played .a leading role at the Nicene Council .

During the 3rd century the wars in which Rome was involved causeslacking of trade between East and West. Persia once more became a major threat to the Roman world. In 260 the Emperor Valerian himself wd a as captured by the Sassanid King, Shahpur I. The confrontation of these two giants, and Romeis need to call and more on the aid of her former subject peoples caused the leaders of Palmyra to come to the logical conclusion that the hour had perhaps come to liberate, the whole of the Middle East from foreign domination whether Roman or Persian. But ways had to be found to do this..

Impelled by an influential Arab family, Palmyra passed, in two or three stages, from being a merchant republic governed by a senate, to being a kingdom under a certain Odenathus the Younger who awarded himself the original title of "King of Kings".

To be sure, his brilliant military actions had earned him the gratitude of Rome: the Palmyrene armies had twice defeated the Persian armies and, in 267, the Senate of Rome named him the "Corrector of the East" in return.

The authority of Oriental Palmyra seemed destined to to extend over a vast territory. But at the end of 267 Odenathus and his, the heir to the throne, were assassinated in mysterious circumstances. Rumor had is that Zenobia, the kings second wife and mother of a very young son, was in some way involved in the crime. In fact, the queen immediately revealed herself to be an exceptionally able monarch. She was boundlessly ambitious for herself, for her son and for her people. Within six years she had affected the whole life of Palmyra. Her dreams of unattainable glory and greatness had brought ill fortune, ruin and .death to the flourishing city.

In 270, the Queen, who claimed to be descended from -Cleopatra, took possession of the whole of Syria, con quered Lower Egypt and sent her armies across Asia Minor as far as the Bosphorus. In open defiance of Rome, Zenobia and her son took the title "August and had coinage struck in the name, thus setting themselves up as rival to Aurelian who was at that time having difficulties on the German borders of the Empire.

The Death Of A Metropolis

They had acted rashly and too hastily. The Emperor Aurelian disengaged from the northern front, raised a new army, crossed Anatolia, hustled the Palmyrians out of their positions at Antioch and Emesa (Homs) and made straight for Palmyra which fell after a few weeks siege. Zenobia managed to escape and fled east, mounted on a dromedary, hoping for help from Ç ,the Sassanids. The Romans, fear lending them wings recaptured her as she was crossing the Euphrates (in the autumn of 272). Zenobia was taken prisoner to Rome where she was forced to ride in Aurelianis -Triumph" in 274. She died soon afterwards, in corn" fortable exile at Tibur (Tivoli), but not before she had learned that a last revolt by her subjects against their Roman rulers had been bloody put down, and that her splendid wealthy city had been pillaged and was due to be destroyed (273). Palmyra was reduced from . being a capital to a mere Syrian frontier stronghoId New walls were built, smaller than those in Zenobiais time, and under Diocletian (293-303), the Romans established a military camp to the west of the city apparently on the site of the palace of Odenathus and Zenobia, which is said to have been demolished and of which archaeologists have so far discovered no trace.

Palmyra never recovered her position. Aleppo, during the Byzantine period, and then Damascus, after 634, from the beginning of the Islamic period, became, in their respective ways, equally important as centers of commerce and ideas. The temples of Palmyra were converted first into churches then into mosques. In the 12th century the walls around the shrine of Bel itself were adapted for use as a fortress. At the beginning of the 17th century, the Emir Fakhr ad-Din was still using ,Palmyra as a place which to exercise his police However he was anxious to have greater security than hat offered by the ruined city, so he had a castle built on the hillside overlooking it. Down below, the ruins .soon sheltered only a few peasants.

In 1751 Palmyra was visited by two English travelers in the course of a long and difficult journey around the Orient. They brought back books of sketches which astounded the contemporary artistic and scientific world. The elegant and mysterious Palmyrene script was deciphered soon afterwards. However, it was not really until our own time, eighteenth centuries after the dramatic end of the Arab Queens Zenobiais . reign, that Palmyra finally re-emerged from oblivion

A visit to the Archaeological Museum which has been installed in a building specially built for it, will answer most of the questions the visitor has been asking him-self as he walked around the ancient city. The items on display have been carefully chosen in order to cover every aspect of Palmyrene civilization through-out the ages; they are many but there is little repetition or duplication. There are informative labels in Arabic and French. Points of particular interest ate illustrated by large charts. There is thus little point in going into detail about the collections in this guide. A few land-marks will be sufficient. The entrance hall is devoted to prehistory - depicted in a series of highly realistic dioramas. The room to the right of the entrance shows the evolutions of the Palmyrene script.

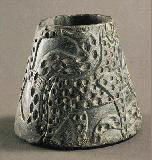

In the next room there are religious sculptures. One of the most beautiful is a carved lintel on which the god Baalshamin, "God of the Heavens", is depicted as an eagle with outstretched wings and smaller eagles by its side, each with an olive branch in its beak; also beside it are figures of the gods of the sun and moon with light beaming from their heads. There is also a great model of the Temple of Bel as it was when it was built. In the third room there are sculptures mostly from public buildings. They depict everyday life, commerce, honors. In them people are dressed either in local costumes: a long down under a wide cloak worn round the shoulders, or in Parthian dress: a tunic worn over trousers tucked into boots. The pack or army dromedaries wear harness very similar to that used today.

The gallery that leads back to the entrance contains many representations of the various gods of Palmyra notably of Yarhibol, the sun god, dressed in Palmyrene costume. The three rooms and gallery on the left of the entrance hall are occupied mainly by splendid funerary sculptures. The actual tomb chests in the hypogeia were sealed by limestone slabs on which the deceased was depicted, as if alive, in high relief, in an attitude of serenity. Various details reveals his social rank or symbolize traits. One hand is generally open, as a token of resignation in the face of death, while the other clasps some familiar object to indicate attachment to life.

In the museum there are many collections of objects explanatory panels, and reconstruction - with life-size wax figures - which together constitute a veritable museum of the Syrian desert and its traditions Certain scenes show everyday life in the oasis of Tadmor, others depict nomadic life which is gradually -disappearing today. Family life is portrayed most real-istically, with all the appropriate clothes chests and tools, appropriately arranged, and models of men and women going about their household tasks. Elsewhere the range of Palmyrene craft-work is displayed - rugs -trays, made of straw, leather and wickerwork. The production of turpentine is also shown, with the special press that is used. The turpentine tree, the rare plant much sought after by Egyptians for the mummification of their dead, grows in abundance on the hills around Palmyra.

In other rooms, camels, Arab horses, tents and the desert itself with the animals that live there - eagles, falcons, wolves, and hyenas - help to illustrate the life of the nomadic Bedouin, a people whose social structures, adapted over centuries to severe conditions of life, have been severely shaken by the development of the economy, by modern transport and by changes in customs and behavior.

A visit to the Archaeological Museum which has been installed in a building specially built for it, will answer most of the questions the visitor has been asking him-self as he walked around the ancient city. The items on display have been carefully chosen in order to cover every aspect of Palmyrene civilization through-out the ages; they are many but there is little repetition or duplication. There are informative labels in Arabic and French. Points of particular interest ate illustrated by large charts. There is thus little point in going into detail about the collections in this guide. A few land-marks will be sufficient. The entrance hall is devoted to prehistory - depicted in a series of highly realistic dioramas. The room to the right of the entrance shows the evolutions of the Palmyrene script.

In the next room there are religious sculptures. One of the most beautiful is a carved lintel on which the god Baalshamin, "God of the Heavens", is depicted as an eagle with outstretched wings and smaller eagles by its side, each with an olive branch in its beak; also beside it are figures of the gods of the sun and moon with light beaming from their heads. There is also a great model of the Temple of Bel as it was when it was built. In the third room there are sculptures mostly from public buildings. They depict everyday life, commerce, honors. In them people are dressed either in local costumes: a long down under a wide cloak worn round the shoulders, or in Parthian dress: a tunic worn over trousers tucked into boots. The pack or army dromedaries wear harness very similar to that used today.

The gallery that leads back to the entrance contains many representations of the various gods of Palmyra notably of Yarhibol, the sun god, dressed in Palmyrene costume. The three rooms and gallery on the left of the entrance hall are occupied mainly by splendid funerary sculptures. The actual tomb chests in the hypogeia were sealed by limestone slabs on which the deceased was depicted, as if alive, in high relief, in an attitude of serenity. Various details reveals his social rank or symbolize traits. One hand is generally open, as a token of resignation in the face of death, while the other clasps some familiar object to indicate attachment to life.

In the museum there are many collections of objects explanatory panels, and reconstruction - with life-size wax figures - which together constitute a veritable museum of the Syrian desert and its traditions Certain scenes show everyday life in the oasis of Tadmor, others depict nomadic life which is gradually -disappearing today. Family life is portrayed most real-istically, with all the appropriate clothes chests and tools, appropriately arranged, and models of men and women going about their household tasks. Elsewhere the range of Palmyrene craft-work is displayed - rugs -trays, made of straw, leather and wickerwork. The production of turpentine is also shown, with the special press that is used. The turpentine tree, the rare plant much sought after by Egyptians for the mummification of their dead, grows in abundance on the hills around Palmyra.

In other rooms, camels, Arab horses, tents and the desert itself with the animals that live there - eagles, falcons, wolves, and hyenas - help to illustrate the life of the nomadic Bedouin, a people whose social structures, adapted over centuries to severe conditions of life, have been severely shaken by the development of the economy, by modern transport and by changes in customs and behavior.

The Great Temple of Bel

The temple is surrounded by a great blank wall, 200 meters on each side, the walls of the fortress that replaced its ancient propylaea during the 12th century. This bleak exterior gives no hint of the magnificence of the buildings internal layout. There is an immense courtyard surfaced with smooth rock, which rises gently towards a majestic edifice at its highest point; this is the cella, the holy of holies, towards which the faithful used to crowed, where the sacrificial mysteries were celebrated. The wall surrounding it lined with porticos whose columns are still standing for the most part, allows one to appreciate the vast proportions of the whole building, but at the same time emphasize the enclosed nature of this shrine to the chief god of the city. The layout of the temple corresponds to the arrangement of Semitic sanctuaries -Thus here there is, in front of the cella, the great sacrificial altar and a ritual basin in which the priests performed their ablutions and in which ritual vessels were washed. The cella was surrounded by a colonnade. Its capitals were made of bronze; only the stone cores remain. The limestone beams joining the colonnade to the wall behind show by their sculptures with what refinement and abundance the building was decorated. Their themes are floral, representations of the god and of processions. One particularly remarkable scene shows a camel carrying a statue of the god Bel passing in front of people dressed in the local costume, a cloth draped and tied around its middle, and followed by a group of veiled women, their heads bowed in reverence. The altar is shown loaded with gifts: pomegranates, pine cones, grapes and a kid. The two worshippers are in Parthian dress. The interior of the cella consists of two open chapels facing each other with ceilings made from single slabs of stone, and richly decorated; the one on the left (as you enter) with signs of the zodiac, the one on the right with very fine geometric designs. The Palmyrene trinity (Bel, Yarhibol, and AglibUl) is also depicted. The arrangement of these two chapels, like two opposed niches, is enough to show original this Palmyrene architecture is, typically Arab and Syrian. Other details noted by specialist have shown that, far from having been influenced by the Greeks and Romans, the civilization of Palmyra, earlier than that of Rome itself inspired both the architecture and the decoration practiced by her invaders.

The Valley of the Tomb

There are enormous cemeteries all around the city, but it is above all on the slopes of the hills to the east that the ancient tombs have been furnished new evidence about Palmyrene civilization. There are four types of burial place to be found here: the tomb-tower (a square structure with narrow windows), the house - tomb (the one that stands in the perspective from the Great Colonnade for example), the hypogeum-tower (a stairway linking a network of underground chambers inside a tomb-tower, and finally the hypogeum tomb, built to receive the bodies of one family over a period of two centuries, a real underground house decorated with frescoes, each cell of which is sealed with a sculpture representing with deceased. There is a guided tour of the most remarkable of the tombs. These include to the north of the city, beyond the ramparts, the so-called Marona house-tomb, behind Diocletianis Camp the Jamblique tomb-tower, built in 83 A.D., and 500 meters further on, up the hill, the tomb-tower of the Elhabel family, 103 A.D. Near the latter, on the edge of the sandy road, is a hypogeum tower, from the terrace of which, in the evening, there is a fine view over Palmyra. Near the top of the hillside there is an entrance at ground level, to the hypogeum of Atenatan which was dug in 98. But the most impressive of all the underground tombs is that known as the Tomb of the Three Brothers (at the beginning of the Valley of the Tombs),which contains some four hundred niches and whose walls are covered with frescoes in a remarkable state of preservation. If you climb the hill crowned by a 17th century fort you wit be rewarded by a magnificent general view of Palmyra the ruins, the market.

The Arab Castles in the Desert

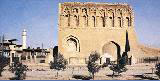

Also worth noting are the two castles some distance away in the desert sands. To the north-east of Palmyra there is Qasr-al Heir el-Sharqi (15 km by an indifferent track, turning off the Deir-Ezzor road at the 99 km post). To the south-west of Palmyra there is Qasr-al Heir el-Gharbi which is more accessible since it lies alongside the track, suitable for motor vehicles, from Damascus To Palmyra, some 40 kilometers from the road to Homs. These castles, both at the same time palaces and military camps, have the same square plan, with round towers at the corners and two semicircular towers flanking the main entrance. They date from the time of the Omayyad Caliph Hisham, who also built a residence at Rasafah, i.e. from about 6889 (the 110th year of Hegira).

The fortified gateway of Qasr-al Heir el-Gharbi has been moved and re-erected in the National Museum in Damascus. The remains of irrigation channels, ruined market towns and cisterns in the mountains nearby, all show that Palmyra was less isolated in years gone by than is generally thought, Recent excavations have shown, moreover, that the hill overlooking of Afqa spring was inhabited by the Amorites from the end of the 3rd millennium. The region has indeed a long and splendid history.

Qasr al-Hir al-Sharqi

110 km north-east of Palmyra, this palace was built by the Caliph Hisham in 628, it contains a palace-residence for the caliph and for the garrisons. There is a small mosque built in the style of the Omayyad Mosque in Damascus, there is a bath with hot, warm and cold running water. This is the oldest Omayyad bath. The palace is surrounded by a wide garden.