From the author's preface to her book: Return to Childhood :The Memoir of a Modern Moroccan Woman

Autobiography, until the last few years, was not respected as a form in Morocco. For Arabs, literature meant the lyric, the poetic, and the fantastic, whereas autobiography deals with the practice of daily life and tends to be written in common speech. As late as the fifties, Khalila Bennouna, the first Moroccan woman to publish a novel, said of the Moroccan writer Rafiqat Attabi'a that she was not adiba (a literary woman writer), because she could not write fiction but wrote about the realities of her own life.

Autobiography was not classified as literature because it was also thought to be accessible to all; after all, the thinking goes that everyone can write about his or her life. Statesmen have done it, as well as artists, especially those in earlier times, who are seen as mere entertainers who ended up as artists because they could not succeed in a real career.

In addition, autobiography has the pejorative connotation in Arabic of madihu naisihi wa muzakkiha (he or she who praises and recommends him- or herself). This phrase denotes all sorts of defects in a person or a writer: selfishness versus altruism, individualism versus the spirit of the group, arrogance versus modesty. That is why Arabs usually refer to themselves in formal speech in the third person plural, to avoid the use of the embarrassing "I." In autobiography, of course, one uses "I" frequently.

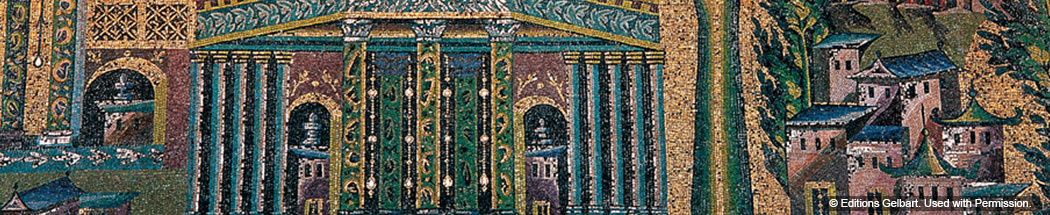

Perhaps even more important, a Muslim's private life is considered an 'awra (an intimate part of the body), and sitr (concealing it) is imperative. As the Qu'ran says, Allah amara bissitr (God ordered the concealing of that which is shameful and embarrassing). Hence, the importance of hijab and hajaba or yahjubu, from the root "to hide," words used for the veil that hides a woman's body and the screen that hides private quarters as in the Qur'anic verse that says Kallimuhunna min warai hijab (Talk to them behind a screen), referring to the wives of the Prophet. The word for the ancient Arabo-Islamic walled city, muhassana, is the same as the term for chaste unmarried women; it means literally "inaccessible." The concern about concealing is clear in Arabo-Islamic architecture, where inner courtyards and gardens are central, windows look inward rather than outward, and outside walls are blind.

In the forties a man sued his neighbor in Sefrou to stop him from building a second floor and he won the case. The irrefutable argument was that the neighbor was going to have access to the man's family's intimacy because he would overlook their courtyard. Autobiography allows everyone to overlook one's private courtyard.

Autobiography must be seen then as an imported genre in modern Arabic literature. It was introduced in Morocco in the 1950s by Ahmed Sefrioui with his childhood narrative, written in French, La boite Merveilles (The Wonder Box). Similar works, also in French, may be seen in Paul Bowles' series of records and translated Moroccan autobiographies: these include Mohammed Chukri's Bread Alone and later Abdelhaq Serhane's Mesouda. The only Moroccan childhood memoir written in Arabic is Fi Attufula (In Childhood) by Abdelmajid Benjelloun, which is set not in Morocco but in Manchester, England, where the author grew up.

For me, writing an autobiography was therefore even more unusual, because I am a woman, and women in my culture do not speak in public, let alone speak about their private lives in public. When I published my first article in a Moroccan newspaper in 1962, I did not even sign it with my real name, but used the pseudonym of Aziza, and when I published my first novel, Am al Fil, in 1983, I left the protagonist's home town unnamed because it was my own.

In other words, I had to wait twenty-eight years before I dared write my autobiography...

The work was meant for a non-Moroccan audience, and I felt it would give me the opportunity to correct some American stereotypes about Muslim women.

I wanted to say that, yes, I am a Muslim woman but I am perfectly capable of taking up the pen to present my own perspective about my country's reality. And, the translation of Am al Fil into English (Year of the Elephant) did clarify some misunderstandings about Islam and Muslim women. As Michael Hall from the University of Melbourne, Australia, stated:

The sheikh in the work, like the text of Year of the Elephant itself, stands in sharp contrast to the lurid images of "mad ayatollahs" and "fanatical fundamentalists" all too common in Western media and academic discourse alike .... In many references throughout the text Abouzeid reinforces an essentially positive image of Islam as a force for social change and liberation. It is of course unlikely that she set out to challenge negative Western stereotypes about Islam when she wrote Year of the Elephant, as the novel was written for an Arabo-Islamic readership who does not share Western prejudices and misconceptions regarding Islamic religion and culture. Once translated into English, however, the text presents an immediate challenge to Western discourse on Islam, opening the question of the role and value of translation within the field of post colonial literature.

An American reader told me, "I thought that Morocco was the Morocco of Paul Bowles, meaning the underground Morocco of hashish addicts and outcasts." This was "the Morocco of 1912" as a Moroccan critic put it.

For these reasons I wrote Ruju 'lla Tufula (Return to Childhood) in Arabic and did a rough translation of it into English. Elizabeth Femea had asked me for a piece of fifteen to thirty pages to be included in an anthology of childhood narratives from the Middle East. At first, I thought that I would not have enough material, for my childhood did not seem to be a source of inspiration. But when I started, memories came back so quickly that I was amazed by their abundance and clarity. The process lasted two months, during which I filled enough pages for a book. When I went back to those pages, I discovered something else. These pages seemed to be of value, and I said to myself, "Why not publish them in Arabic as well?" I called a Lebanese publisher, who answered, "If only they were Brigitte Bardot's." But he confirmed my belief that they might appeal to an Arab audience.

And there was another problem. Since the autobiography had been written for a foreign audience in a sharp tone and in total frankness, I was apprehensive about the reactions of many people, including particularly my family. I put the manuscript away and forgot about it for over two years. When it was finally published in Casablanca in 1993, my family did not only approve but were very enthusiastic. Moroccan readers and critics also received it with enthusiasm. Mohammed Chakir, a respected, young critic in Morocco, classified it as an autobiographical novel because he found features of the novel in it, "multiplicity of voices, nonlinear narration, description, atmosphere, mood, and the poetic."

Other reviewers said things like: "Ruju 'Ila Tufula is bold and courageous"; "its criticism of both the system and the opposition is by far more daring than that of any of the male writers who are active members of the opposition parties"; "Abouzeid is a woman's writer in Morocco, par excellence"; "her female characters are voices rather than images and bodies as they always are in male writings"; and "Ruju 'Ila Tufula gives credit to oral history, an oral history told by traditional, illiterate women."

Since 1993, four autobiographies have been published in Morocco, two of them by women: Dreams of Trespass by Fatima Mernissi and Ma Vie, Mon Cri (My Life, My Scream) by Rachida Yacoubi.

Source: http://www.utexas.edu/utpress/excerpts/exaborep.html#ex1