Mohamed Kamel Hussein

This is the only short story by the author. It appeared under the title Jarima shan'a' (An Atrocious Crime) in the Cairo monthly Al-Hilal , April 1961.

The members of the jury asked one another whether they were entitled to recommend to the judge, if it were at all permissible, that the criminal should be burnt alive. The judge declared that never in his life had he condemned any man to death - no matter what the nature of his crime - without a sharp pang and a deep melancholy: but today his mind was at rest. Indeed, he added, he might even say that he was happy to sentence this criminal to death, in order to wipe away the shame which mankind bore because of this atrocious crime.

The accused was a young man of twenty. Nobody in the small town knew who his father was: he himself had not known him. His mother was a loose woman with a fierce temper, who had lived her life in wretched squalor and poverty.

In misery, she had taken up with a foreign sailor in a distant town; he soon deserted her, leaving her with this son. She had spent her days in a constant struggle to find food for them both, until he was old enough to work. She had made him forage for his own food then, threatening to drive him away if he ever felt too tired or ill, and never sparing him even if he could not find any work.

He was working in a nearby coalmine: and this was a time when coal-mining was a harder lot than slavery. His misery was all the greater because no one showed him any sympathy. What they knew about him and his mother made his workmates distrust him.

He himself was not an easy person to get on with: it was not in his nature to show any friendliness, and he did not join in his mates' talk; a pariah, he was fond of none of them, and was liked by none. The same was true in his relations with older people, and with those placed over him; they gave him the most difficult and most exhausting tasks. He was too poor to buy new clothes: what he wore was so tattered that it no longer even covered him decently. His shoes could no longer protect his feet from winter cold and the filth of mud. He had no supply of water easily at hand, and he would go for months without a wash. People who saw him in this condition, were not sorry for him, but took it that this squalor was his by choice. Indeed, he had become so used to living like this that he no longer cared about improvement, and people assumed that he relished loneliness, dirt and poverty.

He grew into the habit of spending most of his time, summer and winter, sitting upon a stone block in front of the church. It made a cold and painful seat, and he had no covering thick enough to make him comfortable, yet there he always sat until he was too tired or too cold.

This church had become his only link with humankind; yet he did not dare enter it when there were people within. He knew that neither the congregation nor the priests could bear to see him among them; though their religion unambiguously commanded them to accept people such as he, they perhaps judged that this could only be carried out to the letter by those who had the faith of a saint, and that God would pardon them if they refused to make a place for him amongst them.

Once he plucked up enough courage to enter the church on a feast day. As he went in fear that people's repugnance for him was so strong that they would drive him out, to have done as he did was an act of the highest courage. Once inside, he stood in the remotest spot possible, alone in a dark corner, where he was almost invisible to the congregation.

After that, he began to frequent the services, and this was noticed by one of the priests in charge, who considered that it was sufficient Christian charity to allow him to remain in his corner: he neither drove him away, nor gave him any encouragement. Once, during the offertory, the young man came forward with a hand that shook with fear and added to the plate the single penny which was all that was left to him that cay. The priest felt pity for him but did not like to return the tiny amount on the grounds that the donor would need it more than anyone else. The priest almost let a tear fall for this man whose misery and poverty had not made him fail in his duty towards the church. He realized that the single penny was a truer sign of faith than the pounds which a rich man gave. The wretched young man now had the beginnings of human sensibility. He felt that he was becoming a man, that he had so far been an animal that knew only how to eat and drink and perform other animal functions, with nothing to distinguish him from the dogs he saw around him. His attendance at church, giving a penny to the priest from time to time, created this new feeling.

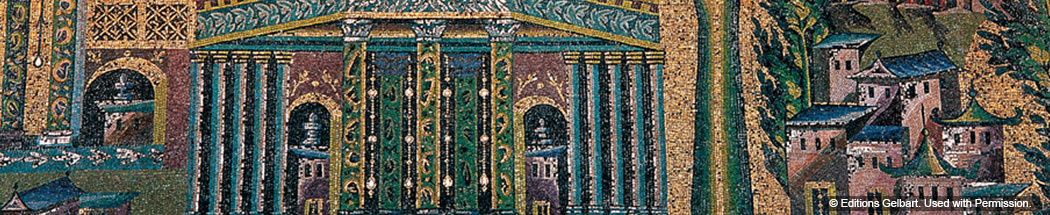

When his anxiety had passed, and he was no longer afraid of being thrown out, he grew to appreciate the beauty of the church, and of the lights that shone in it; now he could listen to the organ and his heart was transported by it, as though he had not heard it before. A second feast day came round: he watched the priests in their beautiful, bright vestments, the women worshipping in all their finery, with their most fragrant perfume: he noticed that the men were considerate towards the women - that with one they were polite and gallant, and with another they let her see that they found her attractive.

This drew him with a yearning he had never known in himself before. He became aware that music moved him, that the beauty of a woman stirred him as much as it stirred the rich, and that he could admire the splendour of the church, and pay reverence to it, just as much as a fortunate man could. This consoled him: ''Whenever he withdrew into himself in this church, he found a haven from the storms of the world, which he had suffered all his life. Then there came round a holiday in the city. He had not been aware of holidays before, and had no notion when they fell: to him all days seemed to be of the same pitch black colour. He sat on his stone in front of the church: the doors were closed, and everyone had deserted it on that dark night. People came and went in front of him, looking their best in their fine clothes. Most of them were making for one of the most splendid houses in the town, where an all-night celebration was being held. Most of the guests had already arrived when one young girl realized that she had forgotten to put on the prettiest of her jewels, and so she slipped home on her own to put the finishing touches to her appearance, then hurried back towards the entertainment. Her path lay in front of the church. As she drew near, he was overpowered by the attractive scent she used, and he found himself stepping up to her, and saying with unwonted daring, "Come and sit with me for a little while."

The girl went pale: she panicked at finding her way blocked by the unkempt creature and was nauseated at the very sight of this person who was asking her to join him.

"Get away from me, you filthy beast," she said.

Excerpt from: Atrocity, by Mohamed Kamel Hussein, Arabic Short Stories, 1945-1965, ed. Mahmoud Manzalaoui. The American University in Cairo, Press, 1985. pp 54-57.