Saheir el Kalamawi

I still remember the small room which belonged to 'Nanny' Karima, my grandfather's black freedwoman. It was furnished with the utmost simplicity, isolated on the roof of my grandfather's house behind a rough wooden door.

As children, curious to see what she was doing, we often wandered into her room. Sometimes we would go there in her absence, tempted by the possibilities of mischief.

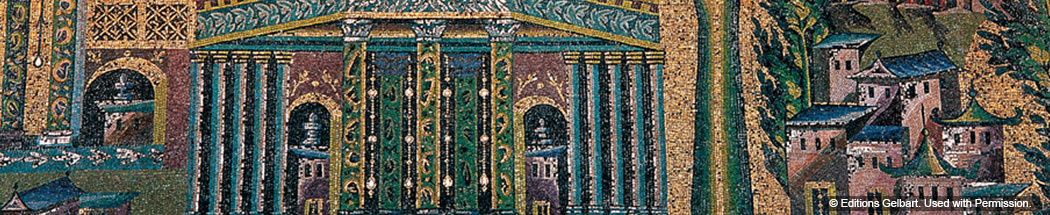

The dominant colour was spotless white. On her head Karima always wore a white head-veil and the bed-sheets too were dazzlingly white. Nothing was hung on the walls, leaving their pristine whiteness undisturbed. There were two windows in the room; a west window which caught the soft rays of the setting sun, and an east window which for a few moments caught the early morning light. So the sun was never seen there for very long. Our particular goal was usually the window facing east, because it looked down onto the lower roof, over the hammam of my grandfather's great house. This roof was inset with upturned bowls of red, green, yellow and blue glass; each bowl being topped by a small, thick, round knob. The sun's rays, striking the glass, were filtered down to the room below as a gentle coloured light that danced on the white marble paving of the large hammam on the ground floor.

This hammam was no longer in use because modern bathrooms had been installed in each of the flats into which some wings of my grandfather's house had been divided. Ever since we had become aware of our surroundings the old hammam had held the aspect of a haunted room, a place of unholy terror, deserted by human beings, but frequented by ghosts and demons. We loved going up to Nanny Karima's to pelt the attractively coloured glass with marbles and pebbles; and when the smashed glass tinkled down to the floor we would shiver with delight. Then, jumping out of the window, clutching an outstretched hand or leaning on the shoulders of the one of us who had gone before, we would peer down through the broken glass to learn the secret of that strange room. What met out eyes was unforgettable, a unique sight. Below us lay a wide marble hall. Against the walls there were thick marble basins; whose rims bore richly veined carvings. The walls also were (.r marble and where the basins touched them they too were decorated with carvings with the same veining. The coloured lights played every¬where with a delightfully irridescent effect.

All this abandoned splendour was coated with a thin film of dust and cobwebs, which gave it an air of age and decay and brought out the magnificence of the tinted marble.

Sometimes we would catch a glimpse of the feathers of a dead sparrow that the hall had held captive until it died amidst such confined beauty, its heart consumed by a yearning for space and freedom.

We felt no aversion for the dust; for twice a day our mother would send us out of her own flat to play in the courtyard of the big house, and there we spent our mornings and afternoons, entirely covered with dust. We felt almost a comradeship with all that dust, and we would wipe it off the glass bowls to make the colours shine more brightly, using the handkerchiefs which were intended for our hands and eyes.

If we were ever surprised by Nanny Karima during these escapades on the hammam roof she would scream at us and threaten to report us to our mother or grandfather. Then, smothering her with hugs and kisses, we would cajole her with entreaties until, at last relenting, she would dissolve in laughter, showing her white teeth, which looked whiter still against her dark skin. Then we knew that she had taken pity on us: there would be no report, no spanking, no scolding. She would wash our hands and faces. When, in gratitude, we offered her the sweets that usually happened to be in our pockets she would refuse laughingly and bless us saying: “God preserve you, little ladies, and little masters!” If we insisted, she would answer more firmly: “God be praised, I have everything I need.”

This little episode would take place again and again, every week¬end holiday, and it must have been one of the principal reasons for our drawing closer to Nanny Karima. Our playing on the roof of the hammam had become a tremendous shared secret which drew us together with her into a hidden order. Karima had no real friends in the household and I can see now that she was afraid we might suddenly stop coming to see her, for our visits were very welcome, even though they could have led to unpleasant results. Had we been wiser we would have known that she would never have reported us. We might have spared ourselves the cautious stealth and dissimulation of our manoeu¬vres. It was more than likely that she would have turned a blind eye to our activities.

Karima was, by nature very quarrelsome and a day never passed without at least one violent argument between her and the staff of the big house. In her eyes they were nothing but servants, but she was in the position of a daughter to the Master of the House himself. She called them lazy and filthy - while she was active, clean and hard-working. We had no conception of the vital part she played in the household. We would simply see her at work in the ironing-room, landing in front of a pile of dazzlingly white washing. She used a long pair of tongs for putting hot charcoal into the heavy iron which she wielded with rapid and energetic movements. It never occurred to us to ask why this work was without end, and we always heard her cursing vehemently when linen had to be starched. The time and effort were more than she could spare, over and above the ironing of table-cloths, bedspreads, blouses and other clothes. Besides all this, she was even obliged to iron the men's suits, as well as my mother's complicated and heavily pleated dresses.

Her love for the children of the household was deeply sincere. Certainly she used to beat us, but I cannot recollect her ever doing so unless it were for that greatest sin of all, dirtiness. How many times she would call out to us, “Children, cleanliness is next to Godliness: are you not true Believers?”

Late one afternoon, there was a slight drizzle and we crept stealthily otway to play among the puddles on the roof. Fortunately for us, Karima was not in her room. As usual she was in the laundry-room, engrossed in her ironing, and the hiss of the stove prevented her from hearing our footsteps. We climbed out of her window, down to the roof of the hammam, and lifted some of the glass bowls out of their sockets in order to let the rain water drip into the room. We hoped it would wash the floor and make it shine, allowing the coloured light free play upon the marble surface. We broke a lot of glass that day, some by accident and some by design. We fought among ourselves to peer through the several peepholes. Our faces became covered with mud as we pressed them against the holes in order to see better, the rain-drenched light being too weak. Suddenly we felt Nanny Karima's black face looking down upon us from her window. This time she threatened, in a voice carrying the utmost conviction, to take the matter up with our mother, “Because”, as she said, “it is raining.” So we rushed to her and went through the same rigmarole which ended as usual at the door of our own flat as if nothing had happened.

Excerpt from: Nanny Karima and the Hamman by Suheir el Kalamawi. Arabic Short Stories, 1945-1965. Edited by Mahmoud Manzalaoui. The American University in Cairo Press, 1985. pp 108-111.