Yehia Haqqi

Zeinab found shopping for her future home as irksome as it was pleasurable. Her cup of joy was not unmixed with tears of a flavour that was new to her. These were sometimes tears of tenderness and joy, mingled with shame at seeing her mother wear herself out to provide her with all that she needed. It was her mother who thought of the jug and basin, the clogs and the bathroom stool. She even bought her two brooms, one long handled, the other short. But Zeinab's tears were sometimes tears of rage, not unlike those of a spoilt child. This was the case whenever her mother drew Zeinab's attention away from natural to artificial silk, saying:

“My dear, this is just the beginning. We still have more important things to buy.”

How the mother would have loved to shower gold and jewels upon her daughter -- but if wishes were horses, beggars would ride.

Theirs was a modest family whose fortunes had declined after the father's death. El Sittt Adeela had refused to remarry for fear of what her only child might suffer at the hands of a stepfather. Highly esteemed in the neighbourhood, she was a woman for whom men would rise to their feet, lowering their gaze in deep respect, as she passed by with her face hidden behind a veil that almost smothered her. In her home¬town, Damanhour, Adeela led a life of self-sufficiency through the sale, by piecemeal, of the five feddans which were all that was left to her. Her daughter's fiance insisted very firmly that she should live with them¬in Cairo, but she refused, saying that she did not wish to be suspected of sponging off a stranger; and she went on to declare that she would remain, until her dying day, in the house where she was born and where she had lived since her marriage. From that selfsame house, her body would be carried out, and her coffin would find its way, unguided, to the grave.

“How can you say such a thing, mother ! I'd give my life for you.” “We all have to go one day, dear girl,” said the mother.

Zeinab grew up under her mother's wing, ignorant of all else in life. To that very day, they shared the same bed, and at night she would fold her arms around her mother and lay her head upon her soft breast…’Dear God, how fragrant her breath was, how sweet!’ There wasn't another soul in the whole world who enjoyed such peaceful sleep. She was proud of her mother who had never in her life uttered a shameful word, nor ever hurt her daughter's feelings.

Zeinab's fatherless state had developed in her a hypersensitivity which clearly displayed itself on the death of the schoolmate who had sat next to her in class. Zeinab mourned her at home, and refused to go back to school unless the headmistress agreed to move her to another desk, even if it meant her Sitting right at the back. So sensitive was she that her distress at having drawn attention to herself was no less than her grief at the death of her classmate.

This, then, was Zeinab, whose love for her mother bordered on worship, a passion which roused in her a mixed thrill of joy and apprehension alike. And yet now she was trailing her mother behind her from one shop to another for her purchases. When her own feet grew hot and swollen, she forgot to ask the old woman, who would be pan6ng for breath, whether she, too, was tired - happiness, like misfortune, blots out all else.

Zeinab wanted to buy a wooden bed she had seen in a furniture shop. What she liked about it was the design on the front, which was repeated on the wardrobe. This motif, common to both pieces of furniture, particularly appealed to her, as it meant that she would be buying a complete suite, not simply two entirely different independent units. She was highly impressed also by the fact that at the head of the bed there were two bedside tables fixed one on either side. She could already imagine her great pleasure as she lay in bed, reaching out her hand for something in the drawer. She would be able to do this, whenever she had neither the inclination nor the time to get up and look for things in some remote corner of the room. She wanted to be 'modern', not like her mother who stuffed everything away between the mat¬tresses.

But El Sitt Adeela firmly refused to comply with her daughter's wishes.

“Do not be deceived by appearances,” she said to her. “Look under the shiny veneer, and you will find nothing but ordinary deal wood which will crack in a couple of summers. It'll never stand the wear and tear of moving house and rough handling in general.”

“The bugs will nest in the wood”, she went on to say. “And why let yourself in for all that?”

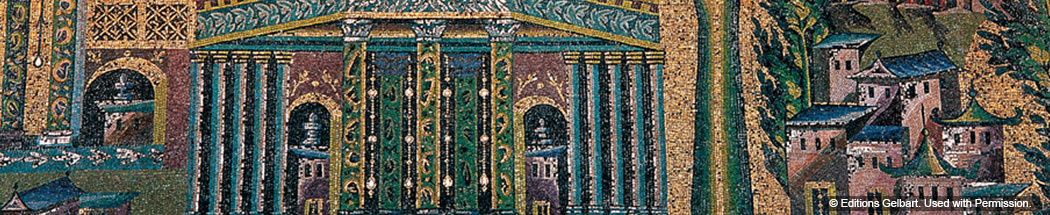

In spite of the tears that streamed down her daughter's cheeks, trickling almost into her mouth, Adeela bought her a magnificent brass bed, not nickel-plated with low angular posts in the modern style, but an old-fashioned brass bed with thick cylindrical posts, all four reaching up to the ceiling. On the top of every post was a huge dome¬like capital. The front of the bed, like the railing round a saint's shrine, was covered all over with an interlacing design of large and small circles, fixed together with nails whose bald heads gleamed brightly. This was the kind of bed to warm the cockles of the heart. It betokened the true gentility of the owner's origins. Only on such a bed could the body find rest. When El Sitt Adeela had sewn a green jacket for the miniature Koran which was to hang from the top of the right hand post, she said to her daughter:

“Now, tell me, if you please, where would we have put it on that stunted wooden bed?”

The brass four-poster was witness to Zeinab's wedding night, and to the birth of her first son and daughter, and of the twins that followed, not to mention her numerous miscarriages. Summer after summer passed, and time began to leave its mark on the brass as it does on wood. The domelike capitals fell off and the tops of the posts now looked like gaping drain-pipes with jagged ends. The shine had tarnished, and lost its lustre. Some of the rings had fallen off, leaving the general design incomplete, and baring the sharp fangs of nails which hurt you if you touched them. But the genteel never lose caste, despite the ravages of time. The posts of the brass bed, no longer upright, stood at an angle, like the legs of a horse that is making water, and the bed jingled as one got in and out of it; but, in spite of the scars and the aches and pains, the bed proudly held itself together, and remained welcoming, generous and spacious. Zeinab and her husband with one child between them, all slept together in the bed - and any of the other children would join them if he was sick. And if you lifted the corner of the mat¬tress, you would find heaps of paper and old rags along with the house¬ keeping money for the month. Like mother, like daughter, when all is said and done.

This bed was Zeinab's refuge, the retreat where she found rest after a hard day's work which began at dawn and continued well into the night. Whenever she surrendered her huge tired body to the bed, she felt as light as a feather, gently falling into the palm of a hand open to receive her. She would pin up her hair and gather it in an embroi¬dered headcloth, ready for sleep, and, before she dropped off, her features, at the idea of repose, would be transformed, and turn into the features of the graceful young girl she had once been, as she slept in her mother's arms. The lips of her wide mouth would pucker up, as though she were sucking a sweet; the tired expression on her face would change to one of innocence and total resignation; and the tone of the voice, murmuring - lullaby to her children, would become tender and gentle, as it never was in the daytime. During the long restless nights when her husband stayed out later than usual, the brass bed provided ample room for her tossing and turning, in her vain search for sleep. Zeinab could not have gone on living if she were ever deprived of that bed. Even on her visits to Damanhour, when she slept in her mother's arms, she still longed for her own bed.

El Sitt Adeela was in the habit of visiting her daughter at feast-times. How delightful those visits were; the children shrieked with joy for them. She used to come laden with baskets of loaves, biscuits, pies, large fresh eggs and a dressed duck whose rich fat was like amber. At night, the mother would sleep on the sofa in the hall, for El Sitt Adeela assured everyone that she liked the sofa because it was suited for all purposes: for sleep, for relaxation, for a siesta and for resting tired legs. If ever a visitor turned up while she was lying down, a slight move to shift the pillow from the head of the divan to the middle was all that was required, and she was ready to receive the newcomer with all due decorum, seating her next to her. There was also a special spot on the sofa for the coffee tray, and the breakfast, lunch or dinner tray if her feet hurt her and she was unable to get up for meals. But why try to justify her liking for the sofa? The fact is that Zeinab's home contained only one bed which stood there in all majesty, and never would El Sitt Adeela consent to the whole family's giving it up for her to sleep in alone, while her dear ones slept on mattresses on the floor in the sitting-room or the hall.

Two days after her arrival on her last visit, El Sitt Adeela had her dinner on the sofa. She ate what was left of the pie, which had turned dry and leathery; for dessert, she had some molasses. Soon after, she felt a heaviness, as though the food were pressing down upon her. Maybe the molasses had been on the turn. She asked for a glass of water with a drop of orange-blossom essence in it, to give her relief; then she dozed off. The next morning, she could not lift her head off the pillow, and when Zeinab felt her forehead, she found her feverish.

“It's nothing to worry about” said El Sitt Adeela in a feeble voice, “I've just caught a bit of a chill.”

Aspirin, tea with lemon, bean soup - nothing helped. That evening, her temperature rose and her body was all of a sweat. Her answers to her daughter's questions grew more heSittant and, at times, they were incoherent.

After a while, she lost consciousness. Tossing and turning, her body, as if on fire, was overcome by a fit of violent excitement. She would have taken flight, but was chained fast. Her head, in continual motion, turned from right to left, as though she were one of a circle of dancing dervishes, and her hands swept upwards and downwards, one after the other, now on her chest, and now dropping heavily by her side like stones. She was in great agony. Zeinab stood pale-faced and dazed, and would have burst into tears if she had not imagined that her mother, although unconscious, was aware of everything around her. If only her mother would scream; that would be easier for Zeinab to bear, than to see her dear one so silent.

Then the tears began to stream down her cheeks, as she saw her mother's hands reaching to tear off her clothes, as though she wished to strip herself naked. El Sitt Adeela, who had lived all her life pure and untainted by any hint of scandal, to strip her body naked!

Excerpt from: The Brass Four Poster, by Yehia Hakki. Arabic Short Stories, 1945-1965, ed. Mahmoud Manzalaoui. The American University in Cairo Press, 1985. pp 76-81.