Salma Khadra Jayyusi

When I think of my childhood, it is 'Akka, or Acre, that first comes to mind. 'Akka has indeed taken on the aspect of a paradise in my memory, although I am not sure I was com¬pletely happy then, even as a child. I do not recall any sense of complacency or full acceptance in my heart of things as they were. In fact, I did all the things girls were not supposed to do. But 'Akka's own original lifestyle, based, in many ways, on a sense of harmony in its people, on a kind of innocent, almost primordial love of merriment and festivity, fascinated me. Beliefs as old as humankind still lived on in that region, side-by-side with newly adopted ones which only people like the "'Akakweh" could have embraced. For example, they still believed that the first Wednesday in Safar, the sec¬ond month of the Islamic calendar, should not find them beneath the roofs of their homes but under the open sky. On that day, they went at dawn to the seashore, even on bleak winter days, with food and music, and there they washed themselves in sea water, perhaps cleansing themselves of the devil, or protecting against disease, as Job had done.

At the same time, the people of 'Akka, during the pre¬1948 decades of the twentieth century, made a habit of pic¬nicking and feasting in al-Bahjeh and al-Shahuta gardens, which were owned by the Baha'is. They were planted with lovely trees, bushes, and flowers and tended by Iranian gar¬deners. Al-Bahjeh was one of the two Baha'i centers estab¬lished in Palestine. Here it was, to the outskirts of 'Akka, that Baha' Ullah, the father and founder of Baha'ism had come to flee persecution in Iran and to establish his head¬quarters. (What better place on earth?) His followers built him a mansion there on the outskirts of the new 'Akka, the modern city built outside the massive walls encircling the ancient town. This mansion in al¬Bahjeh where Baha' Ullah had lived and died was extremely simple, reflect¬ing, in fact, the simplicity advocated by the Baha'is -- quite unlike the more sumptuous Baha'i mansion in Haifa, built on the lovely slopes of Mount Carmel overlooking the Mediterranean, where Baha' Ullah's son, 'Abbas, is buried and which is the site of the world's main Baha'i center even until now.

Every time we went to al-Bahjeh, I made a point of visiting the holy man's sunny and spacious room (such is the image I keep from my child¬hood memory), with its very sparse furnishings, with Baha' Ullah's own bed, a simple mattress laid reverently on a small carpet on the floor, with his slip¬pers still set neatly alongside. There it was, we were told, that he had died, on that very same mattress. But to my child's sensibility, (which otherwise had the tremulous apprehension of the death that took loved ones away), the mattress was surrounded by no aura of death; it rather conveyed, in its utter ascetic simplicity, a kind of vague spiritual message that spoke to my heart. It was there, and in the Zawiya in the old town, the home of the Shad¬hili sufi sect, that I first knew those strange sensations I could not under¬stand, the sudden surging zest and elevation of the spirit, the incomprehen¬sible yearning for something beyond my reach. Reflecting on this in later years, I could see that what I then experienced was a sense of personal com¬munion with an idealized spiritual world, but what I remember clearly from that time is the total loathing I felt, during those moments of secret flight, for everything that was humdrum and habitual.

Just as I was fascinated by the utter simplicity and aloneness of the older Baha', I was equally fascinated by the rituals of the nearby Shadhili Zawiya. Nothing could have stopped me going there on the Mawled evenings when the Prophet's birthday was celebrated with a sacred dervish dance. I stood at the outer window of the Zawiya hall of prayer, gazing with wonder at the men and women dancing inside, arm entangled with arm, in a delirious circle. Each dancer whirled and rolled and swayed dizzily, repeating inces¬santly a thousand times over the two words, "Allah Hayy" (God is alive):

They dance and dance! (1)

finding as they drink together

the taste of ecstasy:

eager feet stepping in

treading out the dance!

so swift they move like birds,

kicking up (their robes)

dervishes turning,

never stopping, spinning!

feet jerking, swaying

in the nets of their robes

like fires of flame!

The Zawiya was the center of the Shadhiliyya Sufi sect, and was controlled by the Yashurti family whose pious and, as I remember them now, angel¬-like women were friends of my mother. It stood in an old building, one of a line of major buildings in old ‘Akka, just inside the walls. First came the great Jazzar Mosque, built by Ahmad Pasha al-Jazzar, probably at the end of the eighteenth century; then to the left, just a two-minute walk away, our school. Then, we were confronted almost immediately by the little minia¬ture hell of the ammim---- the frightening furnace room filled with black dust and raging fire, which fed the famous Basha baths with constant hot water. Whenever we went by, we would see men endlessly feeding this huge fur¬nace, with blackened faces and tattered blackened clothes that looked quite frightening. They would raise their faces to look at us little girls with braids and ribbons flying in the air, running to the Basha baths to buy turmus (lu¬pines soaked in salt water) and pickled lemons from Jillou, the caretaker. Past the ammim on our way to Jillou, we would go through a short, narrow, covered pathway flanked on the right by part of the massive wall of 'Akka's notorious prison. It was with this prison that the names of many illustrious Palestinian revolutionaries were linked, and there it was that many martyrs were executed. Then the walls of the prison curved round, giving way to the Zawiya, with the Basha Baths perched majestically on the left.

Cities have their own characters. Since those enchanting years of my childhood in 'Akka, I have lived, as a Palestinian exile, in very many cities of the world: Arab, African, European, and American, but never have I seen another city with the liberal, merry, outgoing, festive, and compassionate spirit of 'Akka.

The" 'Akakweh" feasted on every possible occasion. Where, in any other town, would you have heard of Muslims feasting on Easter Sunday and even more on the Saturday night before it? The "'Akakweh" called it "Sabt al-Nur (Saturday of light), and we'd go to the big square in the old town where the Great Church was, and watch our Christian friends and neigh¬bors celebrate the imminent resurrection of Jesus. They carried lighted can¬dles, we carried lighted candles. They dressed up, we dressed up. They made Ma’mul cakes, and cakes filled with dates, and we did the same. No one had an oven at home in those days, so everything had to be baked in the public ovens scattered throughout the city. There would be fierce competition during the pre-Easter days, with Christian neighbors protesting at the en¬croachment, "It's our feast!" But we looked forward to it just as we looked forward to the Muslim feasts. The "'Akakweh" had their own philosophy of life, and, being only eight when I went to live there, I embraced all the habits and customs of a true citizen.

And it was in 'Akka that I first discovered my adventurist spirit. I used, for example, to take the short-cut to school along the city walls-a path strictly forbidden to us girls. The massive walls of 'Akka were surrounded by two moats separated from each other by what seemed like an artificial hill but which must, in fact, have been the original terrain before the moats were dug. In the old fighting days, the two deep grooves would be flooded with sea water, making it extremely difficult for an enemy to cross. Our house was about thirty yards away from the outer moat, which was planted with quinine trees to discourage mosquitoes from breeding in the damp trench. In the middle of the groove was a pebble path to the "hill" which separated the two moats. Then, on top of this barren, dusty, extremely rugged eleva¬tion was a narrow pathway twisting and winding all the way around various smaller elevations that popped up here and there, hiding whatever was be¬hind them. This pathway eventually led to the main street of' Akka. Because I was always late leaving home for school in the morning, I almost always took this road and was probably the only girl who ever did so on her own.

"Are you mad?" Amm Muhammad, our cook, would say, "It's used by the workers and the fellaheen (peasants). What if some rough fellow attacked you?" I'd shrug my shoulders. "They never do," I'd say. "I like the fellaheen. They'd never hurt me." And they never did. I cannot describe the secret joy I felt as I walked along that dusty road, and the dreams I spun in my head in that state of total aloneness: an aloneness emphasized a million times over by the fact that I was walking in a domain where no girl ever walked on her own. I felt utterly free. My sister Aida never joined me in these adventures. She was always respectful of the rules and conditions of a life which, even in our relatively liberal home, was a difficult one for girls. Our cook never told on me. But my mother heard of it from the neighbors.

My mother tried to channel my wayward streak in what she saw as the right direction. A great storyteller, she would tell me tales (some she had read and some she had invented) which she thought would foster an ideal¬istic attitude in me. She idealized love; after all, she enjoyed my father’s love, fortunate woman, until death parted them in 1954. She also idealized na¬tionalism, poetry, selfless endeavor, and the capacity to strive for a good cause. She detested, however, the quest for wealth and material goods; for¬tunately, she never lived to see the mad pursuit of wealth which infected the Arabs after the advent of oil. Just before her death in 1955, she told me how much she had worried about me when I was a child: "You seemed so fear¬less, so strong-headed, always going your own way." She also always empha¬sized the need for perfectionism: "Either do a thing properly, or don't do it at all." I loved this principle and took full advantage of it too, using it as a pretext not to do things I was not inclined to do. I think she knew this---

¬I would see the realization flash in her eyes-but she'd let me off the hook. Later on, under the guidance of Sister Guida, the German nun at Schmidt's Boarding School whom I idealized, I came under the same kind of insis¬tence on perfectionism.

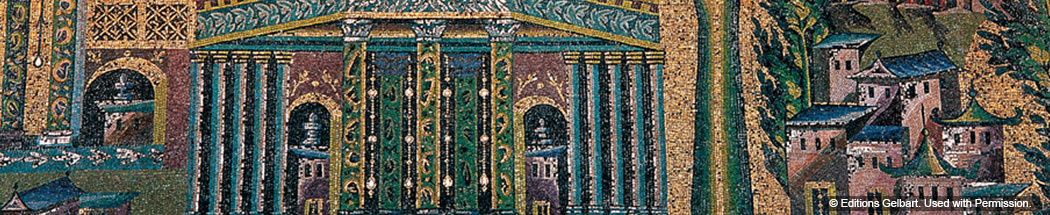

The Jazzar Mosque was the very heart of' ‘Akka. Situated just inside the walls, which had been partly demolished in modern times to make way for the asphalt road, it was big and majestic, with two gates, a main gate and an¬other opening onto the blacksmith's suq. It had many rooms in which male students lodged, two to a room, and was elevated so that one had to climb a wide rounded stairway of seven or eight steps into the large open court¬yard with the ablution fountain in its midst. At the side of the stairs was the sabeel al-tasat ("the vessel fountain"), a once beautiful fountain with a frieze and about fifteen small basins with an equal number of metal vessels, each attached to the basin by a long chain; those passing would drink the cool, constantly refreshed water. Drinking from these vessels was forbidden by Mother. A doctor’s daughter, she had a keen sense of microbiology. This was perhaps the only prohibition I faithfully obeyed.

It was in the courtyard of the Great Mosque that the first anti-Mandate, anti-Zionist demonstration convened. Men and veiled women met there, delivering many enthusiastic speeches (some of them by the women), then going on in a huge procession to the Three Martyrs' Graves at the main cemetery near the public gardens; in fact, all demonstrations came to in¬clude a march to this spot, which was treated almost as holy ground. And it was in the offices of the mosque that my father’s office was located. He had been appointed director general of the Islamic Waqf the religious en¬dowment of Galilee, whose headquarters was the Jazzar Mosque. He loved being there, as the mosque had, in its lower cells, extensive archives. He was then completing his exams for the bar as a mature student; he felt it was im¬portant to be able to combat the Zionist aggressions on Palestinian land in a formal, legal way. Although he fought, with all his strength, against Brit¬ish policy and the British presence in Palestine, he had the highest respect for the British legal system, believing it to be independent of the political arm and to be characterized by integrity and justice. He felt that legal struggle was a sure way of regaining land acquired by the Zionists in illegal ways; and he was highly successful in this effort later- only to lose every¬thing again in the upheaval of 1948! While still working as director general of the Galilee Waqf, he familiarized himself with firsthand information about the lands in Galilee and their rightful owners, information contained in those old archives.

We sometimes visited Father at his offices in the mosque. But there was a special trip I often took to the mosque which remained a secret.

In the mid-eighties, my two daughters visited me in 'Akka, where I was staying briefly. They both spoke at once: "We stood on the very spot, Mother, where you must have stood in fear so many times, holding back your tears. We went to the Jazzar Mosque, and a very old man with a hoarse voice showed us where Grandfather's office was and where his desk had stood. He said he used to serve coffee to Grandfather there." Was the man Shaikh Sa’do, I wondered? To my child's imagination in the mid-thirties, Shaikh Sa' do already seemed old, one of the legends of 'Akka. He was care¬taker at the Great Mosque, but also served as a factotum for my father. Shaikh Sa'do had liked me at first, always laughing when I sang the song written about him by a worshipper who had lost the new shoes he left at the gate, as Muslims must do before entering a mosque:

Shaikh Sa'do, listen to me.

My shoes were stolen from me.

My shoes were black and shining,

among the shoes of the crowd;

were it not for shame and cleanliness,

I'd have put them in my breast

The song had bouncy rhythms and rhymes, and the young girls used to sing it at our school and giggle. But I dared to sing it straight to Shaikh Sa'do him¬se1£ Soon afterwards, though, our friendship came to an end when a funny little story was circulated by Baghbaghan (which means "parrot" in Pales¬tinian colloquial). This Baghbaghan was the town's gossip. If you wanted the whole town to know something, you let her hear about it. She had been widowed, and it was said that the missing half of her middle finger had been bitten off by her own son in anger at her spiteful tongue. It was supposed she was happy with her constant daily round of all the prominent families, who welcomed her, though half in terror of her tongue. Great was the sur¬prise when it was rumored that she coveted Shaikh Sa'do. I wondered if any¬one could covet that rugged, unceremonious fellow with the hoarse voice?

My father used to send him to her with a monthly stipend from the Waqf money, and the story had it that on one of those occasions she said, "Shaikh Sa'do, let me put my cheese on your bread and let's make a life for ourselves together!" He was horrified. "Shame on you, woman!" he barked, then ran away. But she, true gossip that she was, told the story to some other women and, when I heard it being told to my mother, I couldn't stop giggling. When¬ever I saw Shaikh Sa'do after that, I would murmur cruelly, "Why don't I put my cheese on your bread, Shaikh Sa'do?" and burst out into uncontrol¬lable giggles. And from that time on he avoided me.

"We tried to work out the very spot where you must have stood," my daughters continued, "just opposite the corner of Grandfather's office where his desk was. And we saw the minaret, too. Then we went to the school building and walked along the same road you must have taken that day you told us about." "You tried to live that experience, then?" I asked them.

But no one can. It was one of those utterly terrifying experiences that take over a child's whole being, and even now the memory of it can still shake me.

It started one day at school, when I was almost nine. We heard the adban call from the nearby Jazzar Mosque at ten-thirty in the morning. But that was no time for adhan. What did it mean? The teacher explained that this was not adhan but tadbkir, an announcement that some dignitary had died. In the recess, I went to the teacher. "If you please," I asked, my voice break¬ing, "Would they say tadhkir if someone who had helped found a party died?" "A political party, you mean?" she said. "Of course. Every minaret in the whole of Palestine would announce it." From that moment on, the tadhkir was the repetition of a constantly renewed nightmare. My father was a political activist, and one of the founders of the Istiqlal political party. If he should die, I reasoned, tadhkir would certainly be said; and so when¬ever I heard tadhkir, I would go tremulously to the teacher and say in a tone so decisive as to leave no doubt in her mind, "Tridi, if you please, I need to go out." She always let me, and down the stairs I would tumble. Then I stood behind a wall until Amm Ahmad, the school porter, had turned par¬tially away, which is when I would run to the huge gate, open the small door in the left half of the gate, and dash to the mosque. I would run up the few wide stairs near the sabeel fountain and stand in a place where I could see my father when his door opened; then, the moment I saw him busy at work, I'd run back to my class again like lightning, often hearing Amm Ahmad's scold¬ing remarks about "those who come so late to school."

Once, as I had begun crossing the large middle room at home (the liwan, we called it), I heard Father tell Mother, "It's as if, every now and then, I see Salma a long way off, while I'm at my desk. Then, when I go out to look for her, I find that she's disappeared without a trace, like a little genie." I looked at him, feigning complete innocence, but still he persisted, "Yes, 1'd see her, red ribbon always loose on one braid." 'That's Salma all right," Mother laughed. "You must be thinking of her all the time, and so you see her phantom everywhere, with the red ribbon loose on her braid!"

But he caught me at the end. I was standing in the usual place, but when the office door opened, there was no trace of my father. Had he perhaps gone to fetch a book from the opposite wall? I waited. Was he perhaps sit¬ting with some guests in the opposite corner? I waited, Was he . . .? Time passed, but wild horses couldn't have moved me. I fought back the tears welling up in my breast and stood there, mesmerized, for probably fifteen minutes. Then, all of a sudden, two hands were laid on my shoulders and a most welcome voice called my name, "Salma, what are you doing here?"

My mind worked frantically to invent a quick excuse. "Baba," I wailed, tears of relief and embarrassment gushing out like torrents, "Baba, I am huuuungry!"

"That was very clever of you," my mother told me many years later. "You knew his preoccupation with feeding his family properly." 1'd realized it, of course, instinctively. He'd often been hungry himself when he was a boy.

My grandfather had died when Father was very young, and he'd been left in the care of his older brother, Uncle Fayyad. A very handsome man of great piety and patience, Uncle Fayyad had married a girl from a poor back¬ground, and everyone around her suffered from this lady's memory of her impoverished early life. The marriage had been my grandmother's deliber¬ate choice. During the First World War young Arab men were conscripted into the Ottoman army, but the Ottomans had also made a law that any young man married to a woman who was poor, orphaned, and had no adult male relative would not be required to join the army. Three of my grand¬mother's four unmarried sons were old enough to be conscripted, and so she searched far and wide to find "suitable" wives, coming finally to Sidon (or was it Tyre?) to select the wife for her oldest son. Having been poor all her life, the lady continued a tradition of penury, and my father suffered at her hands. Later, as a boarder at the Sultaniyya School in Beirut, enjoying the freedom of his own actions for the first time, he had, on his weekly outings from school, to choose between buying a book, or some delicious fateereh pastry or a piece of kubbeh in the bustling, colorful Beirut market. He often told us how he would stand pondering for a while, his stomach screaming for some delicacy, but how he would invariably buy a book instead. He was never going to let us suffer hunger, or long for something to eat, if he could help it.

So I, instinctively, exploited his preoccupation. He immediately called Shaikh Sa'do who came warily toward us, and, not realizing the broken state I was in, avoided looking at me. "Ahmad," Father asked, turning to his companion, "How would you like to have an early lunch with Salma?" It was already past eleven o'clock. "Shaikh Sa'do can bring us some nice grilled kabab and hummus, with some turshi [pickles] and olives." His friend very readily agreed. He was Ahmad Shuqairy, who, in the sixties, became the first leader of the PLO, but at that time was a young, aspiring lawyer at the be¬ginning of his political career. By a happy chance, my father's companion was bent on talking politics during that miserable lunch, and two Palestin¬ian men talking politics had no time to notice a still petrified little girl chok¬ing on her food. I couldn't swallow a thing, but the two men were happily absorbed, eating in an absentminded way, enjoying the discussion. At last the ordeal was over. "Have you finished, sweetheart?" Father asked. I nodded in the affirmative. "Shaikh Sa'do," he said, "take her back to school." Then, turning to me, he produced a shilling and said, "Here, buy some sweets."

Shaikh Sa'do walked miserably on at my side till he realized, from my sullen silence, that he was in no danger. "What is a little girl like this brood¬ing about, 0 God? What could have upset her so?" he kept murmuring as if to himself I, for my part, was thinking hard. Jolted and thoroughly de¬moralized by my experience, I now felt ashamed of all the trouble I'd caused, of the meal I'd forced my father to buy, of having lefr my mathematics class when I needed to concentrate on it. Suddenly, a kind of a deep-rooted ra¬tionality took hold of me: "I'll never humiliate myself like this again! Never again will I listen to the devil. My father wasn't going to die. Of course he wasn't!" I decided then and there, as I walked alongside a sympathetic Shaikh Sa'do, never to give in to this kind of fear again. And at that I felt the surge of freedom rise once more in my breast. My old mischievous spirit took hold of me again, and I looked at Shaikh Sa'do, my eyes twinkling, "Let me put my cheese on your bread, Shaikh Sa'do," I hummed in a low voice, and burst out into uncontrollable giggles.

Note: I checked these memories with Muyassar Abu 'I-Naja (Imm Riyad), who lives now in Boston but who was originally from 'Akka and went to the same school as I did. I owe her many thanks for refreshing my memory.

(1) From "Birth," by M. M. al-Majdhoub, translared into English by S. K. Jayyusi and Charles Doria. Published in Modern Arabic Poetry, an Anthology (New York, Columbia University Press, 1987, 1990).

Reproduced from Remembrances of Childhood in the Middle East, University of Texas Press, with the author's permission.

In 1980 Salma Jayyusi founded PROTA (Project of Translation from Arabic Language). The novels, short stories and essays published by PROTA include: Modern Arabic Poetry; The Literature of Modern Arabia; The Legacy of Muslim Spain.