Houda Naamani

What I have been asked to remember I hope constantly to forget. A great nostalgia for my birthplace, Damascus, haunts me in my dreams, fills me with sadness, questions, and an¬swers that make me sometimes fear that a source of beauty and respect is gone forever. A page from the history of our country, a page rich in dignity, honor; tradition, and magic has been dramatically turned.

During the thirties, Damascus was the spiritual wealth that meant to me, as to others, happiness, values, stability, and contentment. It summarized the East for us in its pri¬vacy, prejudice, and seclusion. Syria with its castles and pal¬aces. Lebanon with its mountains, rivers, beaches, and mead¬ows. Iraq with its mosques, deserts, and palm trees. Egypt with its Nile, pyramids, temples, its warmth of spices, cot¬ton, and wool. The Arabian peninsula with its pearls, rubies, and the power of its holy places. Like one large, whirling circle, the windows, doors, and rocks of all these countries carry a hundred stories about dervishes, traders, caravans, conquests, knights, silk, velvet, perfumes, incense, mer¬chants, and pilgrims. Here in this land is the trace of Adam's fall and of the blood of Abel, who was murdered by Cain. Here is the water which was transformed into wine by Jesus Christ. Here the head of John, still gazing at the world, was presented on a silver platter. Here is where Mohammad stopped and said, "I won't enter paradise twice."

Yes, Damascus, to me, is the beginning and the end of Creation, the throne of God. When I close my eyes, I see old Damascus as a flower from which life sparkles. Every dawn the windows and doors were opened. The streets were crowded with men going to their jobs, children going to school, women bustling to shop for what they needed. Sounds of carts and horses, drifts of scents and perfumes. Singing by the vendors.

A beautiful beginning. A general agreement among people about appro¬priate habits. For every job its clothes. For every village its summits. For each place and state its accents. Then, the same language, dreams, and mem¬ories did unify everybody.

I close my eyes and see Damascus wearing the confining garb of the night illuminated by the light of the minarets; I hear the murmur from the mosque's readings. For each month its ethics, motives, congratulations, and cakes. For each time its invocations. For everything, its fixed time-its claim for meetings, for fasting, for prayers, for parties, for marriages; even for burial there was a specific hour. In those days, Wednesday was not the time to see a sick person, and Monday was the day to clean the house. And by 10 P.M. women were driven away from the roofs of their houses because that time had been set for men to sell doves.

I believed then that these routines demonstrated love, universal beliefs, justice, truth, and stability. How could I have been so naive and so ideal¬istic? Why did I not see in the cultural, political, and economic opening to the west a new age that blew away the life and nature of Damascus? Travel, new languages, technologies, factories, electricity, offices, schools-all of these things were the beginning of separations and differences between so¬cial classes. How was it possible for the success of the Arab Revolt to lead to the division of the Arab countries (after the Sykes-Picot Agreement), to result in a convulsion that changed everything? How could the Mandate not be a shame, horrifying all those -who are today so proud of the past? How could Damascus defend itself after these transformations which caused many other changes, changes in which stronger countries had a hand?

Why did I not notice these dangers when I was living in the midst of them? Did I not understand in my happy childhood that I was living not on a mountain rooted to the ground but on the back of an animal which was being pushed to move? For me, then, the Mandate was a toy, a distrac¬tion, a passing shame. I was proud of my French school because it was a temple of learning. Every day we were told that French culture was an ex¬ample of orderliness that should be followed. France was the most beauti¬ful country in the world; its history and literature the greatest. I still remem¬ber Victor Hugo's poems that we had to memorize.

Am I wrong to wish to forget this dilemma? My own family was govern¬ing the country at this time, so I was part of this conflict and irregularity. The conflict was dangerous, like playing with fire. Who is with whom and who is against whom? Where is strength? Who is capable of staying strong? Who could save the country? Who knew the past? Who knows the future? Where was hope and safety, good and evil? I did not understand that the period of my childhood was the beginning of another era, of another dan¬ger, of another war. I did not see that all the world was beginning to change.

As a child, I believed it was normal for my house to be the biggest one in the district, to be open day and night, full of people, for political meetings and parties. I never judged my family's life. I believed that there was a logical~ reason for our wealth and social separation. Since Mohammad until now. Since the Ummayads until now. Since the Abbasids until now.

The families of Damascus were like a forest. Each family had its tree. The past was very important for the present. Only those who could trace their descent from Mohammad and his family were nobles (ashraf) and held titles and positions. And those who had noble lineages plus politics, land, and knowledge were the most lucky. By chance --only chance--we were one of those families. With this lineage, I thought we were invincible. Is not this a reason to try to forget?

In those days, pride about origins made all life choices very fixed, very direct, very easy. This was true for every relationship, especially marriage. Couples should come from the same class. Jobs should be suitable to social position. Such traditions and beliefs controlled everything. How could I not have noticed in other children's eyes other dreams, other hopes of bet¬ter and different lives? At the time of political demonstrations, students from other schools would come into my school, throw stones at the windows (aiming for our hearts), run on our stairs, and knock at our doors. They asked us to come out, to share the revolt with them and cry, "Injustice!" Afraid of their anger, we would leave when school closed to go home rather than join the protests. We did not understand that these sounds were not an expression of despair or weakness but the beginning of a conflagration that would destroy all the old principles and traditions and establish a new Damascus.

I did not understand the students who were protesting. I considered Da¬mascus a paradise--my paradise--which was eternal and able to remain strong against any wind. Political differences, I felt, would be solved at the right time. And we were sheltered from these problems.

What did we feel when the streets were closed, when officers were pelted with stones, when nobody was allowed to go out? What was the govern¬ment to do, we wondered, meet the protesters and ask what they wanted? We had been taught that every demand had a right to be realized if possible. But I thought that what was happening then was only a cloud which would eventually pass away.

Damascus was paradise for wealthy people. Differences in religion did not imply enmity to me or my family then. I looked at it as a way of know 1¬edge, of richness. Most of the people who visited my house were Christians: the teachers of piano and language, the dressmaker, close friends who were artists, judges, doctors, and lawyers. Religious difference did not exist in front of food or laughter or poetry. Difference of religion--what was that? I never thought about it.

The difference in Muslim religious principles did not seem to be a prob¬lem either. Because the Sunni Muslims were the majority, we had no reason to question differences between Muslims.

For me, then, life was peace, perfection, and blessing. I thought that with the smells of coffee and the sounds of money came love, friendship, respect, and understanding.

As a child I lived behind a mask. I never tried to understand what is frightening and hurtful in life or to worry about what I did not know. Our house was heaven! What made me angry was if the servants did not answer when I rang the bell or if one of my dresses was not ready to wear for a joy¬ful party. I took for granted my good fortune and even my good grades in school.

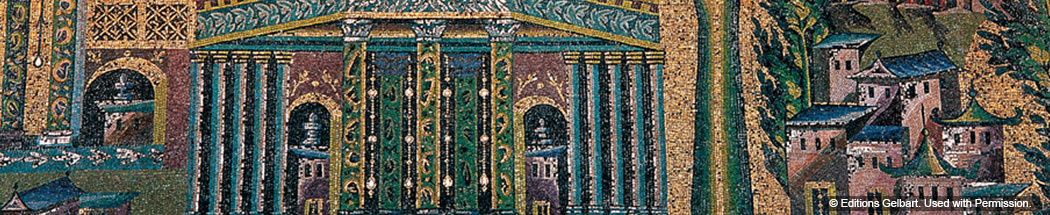

Oh God. In my memory, life was beautiful, perfect, innocent, and peace¬ful. There was no place for fear and danger in our house. The twenty rooms could hold hundreds of people. Tree-lined gardens had fountains fed by majestic stone lions. Tall pillars decorated the walls. There were pools of water, rooms of inlaid tiles, and doors made of carved wooden stars. Blue opaline lights hung from the painted arabesque ceilings. As they played with the water, the trees, and the colorful marble floors, the sun's rays illu¬minated the lemon trees, the thick grape vines, and the tall pots of flowers.

I remember all that. I remember also that I was an object of love, for I was the youngest, the child who had finally come after seven long years of waiting. All the love that used to be given to my mother-who was every¬one's favorite-was given to me. This love protected me like the walls of a strong castle. I thought nothing could penetrate this earthly paradise, even death. However, I was wrong.

The sound of water only suggested nature's continuity. The sound of doves suggested a relationship between the earth and the sky. The playful¬ness and laziness of my cat Fulla created continual moments of tenderness. My grandfather's cloak was a symbol of the strength and greatness of the big house. The sound of my mother's slippers, decorated with feathers, sig¬naled seduction and warmth. And stories! What stories were told in my house. Stories of pilgrims that my grandfather Gazzi led to Mecca nine times successively. About the caravans headed by the Naamanis which came from Beirut to Damascus on their way to Palestine and Egypt or to Iraq and Arabia. The tale of my parents' wedding in Beirut that lasted for seven days and continued in Damascus, where all the city's population was invited and many people took the train back and forth to our house. Stories about King Faisal or about Said Basha EI Yousef (my grandfather's cousin who was the governor of Damascus). Jokes about this old, rich, and authoritarian age. Summer and winter provisions came on camels filling the streets, bringing food from my grandfather's estates: onions, potatoes, lentils, burghul, wheat. Horses carrying pots of honey and butter, tomato sauce, olive oil, baskets of eggs, milk and cream, sacks of bread, and watermelon.

Because of the nature of the era, work seemed a fantasy, not an obliga¬tion for everyone. The big door of our house stood open to welcome and help people. My Uncle Said, who was a minister and first deputy in the Par¬liament used our street to deliver speeches and meet people during his elec¬tion campaign.

I was seven years old when I shared these events and spoke at a politi¬cal meeting my Uncle Said had set up at our house for Shukry Kouatly. I memorized a poem to recite, a poem written by Wadi Talhouna, my private teacher of Arabic literature. On the day of the party, the servants put on their best clothes. They set up chairs in the big garden, and a big table on top of which I was to stand. My mother worked with two dressmakers, preparing my dress. I was shaking. But I knew I must not fail. For I was supposed to be the star of the evening.

My father saved me.

“Do you see those chairs?" he asked.

I nodded.

“There are seven hundred of them. Nobody's sitting on them now, right?”

I nodded again.

"When people are here tonight I want you to imagine them empty."

And it worked! I was fine.

But I did know that war might come and take me away from these wonderful moments. Nothing stopped disillusion. Not even the stories of A Thousand and One Nights. Ends would come slowly in the darkness. Reality might grab you, take you by the shoulders, or strangle you and thus tell you the party’s over. This is how the years fall away, or jump like a cat in the darkness, or disappear and reappear, like the voices that I still remember.

It was my aunt, speaking to my mother.

“Salwa, SaIwa, what happened? I saw your light on and heard noises, so I came,” she said, coming from her apartment to ours.

I jumped out of my bed and opened my door. My mother was taking a pan of hot water from Amina, the youngest servant; my father was smiling, although the traces of pain were clear on his face.

"Go back to sleep," he said to me.

My mother said to my father, "Fouad, you sat near the lake holding Hoda's hand. Why don't you care about your health? The cold and the hu¬midity were bad for your kidney. You're just like the children."

“Salwa, don't exaggerate, I'm fine," he said, and added to my aunt, "Did you finish your makeup?"

To lighten the mood, my mother said, "Ihassan needs two hours to dress and two others for the makeup. There's a strong friendship between her and her mirror."

I did not laugh as the others did.

My grandfather came out of his room wearing his black cloak. "Maybe he's just exhausted," he suggested. "This month was very hard for him. Why does he make himself mad, trying to set up a new law for the farmers? They always rob us."

"He asked me to go with him to Beirut. I said no. Maybe he's mad be¬cause of that," whispered my mother.

"Stop analyzing. It's just the cold," said my father.

"It's not only the cold," said my mother. "You've lost fourteen pounds on this diet. We should try another way. I will call Dr. Roshdy immediately."

I went close to my father. I put a hand on his chest and told him, "Do not feel sick," and I went on to add, "Do not leave us." I was afraid. I did not sleep that night because I dreamed a woman in black was trying to get in my house through the windows. In the morning, my father did not watch me eating my breakfast and taking the big bus to school as he usually did.

When I came back from school he was still in bed. Around his eyes were big black circles. "Did the doctor come? What did he say?" I asked.

"Nothing, he is fine," said my mother.

But he was not fine. After a few days he felt better, but after that he be¬ came worse week by week. His handsome face paled because of the medi¬cine. Even Arabic formulas did not make him feel better. After months without any improvement, the doctor decided to take him to the American hospital in Beirut. When my mother told me this, I cried very hard. I asked to go along but they would not let me go because of school. They came and went more than once. To me, my father seemed to be traveling far away.

During the holiday of the new year, we had a tree and my father deco¬rated it with numbers and colored balls. However, the dark circles around his eyes were bigger and bigger. He became the central subject of interest for all the people in the house. Silence for Fouad. Special food for Fouad. New pajamas for Fouad. A new clock for Fouad. Nothing else was interesting. The political problems, the loss of a crop because of rain, the fight¬ing between my uncle and his wife, and the threat of their divorce became less important. My father's sickness and suffering were the most important events for everybody. Everyone was especially nice to me --- as if a catastrophe was about to happen.

The catastrophe took place on February the fifteenth. They took my fa¬mily to Beirut for the operation. That night I saw in my dream a black owl making horrible sounds up on one of the trees in my house. And in my dream suddenly the owl left the tree to sit on my chest and started screaming in my face. I shouted, of course, and cried so hard that the bird left. More than one person came into my room to see what was the matter. But what could I say? Could I say that a bird came from my dream to sit on my chest? That his eyes, his mouth. . . I started crying. Suddenly the electricity went out. They brought candles and tried to calm me down. However, the bird's smell did not leave me and I sometimes still hear the sound of those wings near my face.

I got up in the morning. It was clear to me that I was not the first child to have this dream. The stories of my childhood contained many similar examples in which walls crouched and objects spoke. These were nights, the magicians used to say, of battles between evil and good, innocence and in¬justice, peace and war. Was the bird a messenger of bad news? Was it singing of the possibility that the sky could be opened? I remember worrying about what I could say and whom I could tell about what happened.

I was getting ready for school. I was combing my hair and looking in the mirror when the blue ashtray I had given my father months before fell and broke. I became frightened. No one had touched it. It broke by itself, but who would believe me? A few minutes later I heard noises. Someone was running upstairs. I heard my uncle saying, "In the night at 2 A.M., Fouad left us.” I was eight years old. He was forty-two. He left by himself. And the old Damascus left with him.

Reproduced from Remembrances of Childhood in the Middle East, University of Texas Press, with the author's permission.

Houda Naamani is a distinguished poet and painter. Her paintings have been exhibited in Washington, London and Beirut.

Her website is www.houdanaamani.com