February 1987

When the war began, I was barely in my twenties. I lived at home, pampered and protected. I was studying at the university and had found a part-time position that paid very well. My father was very proud of me.

Like many Levantines, our family’s history was complicated. Both my parents were born in Alexandria. My mother’s parents were Greek, and my father’s Syrian-Lebanese. First class exiles in a multicultural and multilingual Egypt, their world collapsed just as they were laying down roots in a serenity that was not to be. They suffered a second exile to an Australia that was welcoming in form but not in substance. Their third move to Lebanon wasn’t a formal exile, but had all the substance of one. Each country they moved to made them strangers again, beginners in the business of finding jobs, a school, a home. Every move meant their having to start their lives from scratch.

I am sharing this long preamble with you to explain how much the war that came so clandestinely into our hitherto prosaic lives cost us. We were barely settled in our new apartment on the sixth floor, with a balcony overlooking Beirut and the Mediterranean, when we realized that the upper floors of buildings in this city so quickly torn apart by war presented both dangers and advantages.

On to February 1987 and the street wars of West Beirut. We had just finished our Sunday meal and my mother was putting away the dishes when we heard a knock at the door. Years of power outages had struck Beirut doorbells dumb. I opened the door and found myself facing four armed men. I recognized one of them. He lived in the neighborhood. "We do not want trouble. We have orders to see your balcony," said the neighbor, who worked as an apprentice to the mechanic down the road.

My father, visibly upset, tried to block them. The mechanic-turned-militiaman, who was blond with green eyes, pushed my father aside and tramped into the apartment. He pointed his Kalashnikov at my mother. "Go into in the kitchen,” he barked.

My mother had tears in her eyes. "Ya ebni, wahyatak…" She said with her broken Arabic.

"Yalla! Fouti! " he growled.

We obeyed without a word.

The armed men spent three days in our home.

The battle was vicious. The men settled in the bedrooms that extended to the balcony overlooking the narrow streets of Zarif and shot at their enemies-du-jour, who obliged with equal generosity.

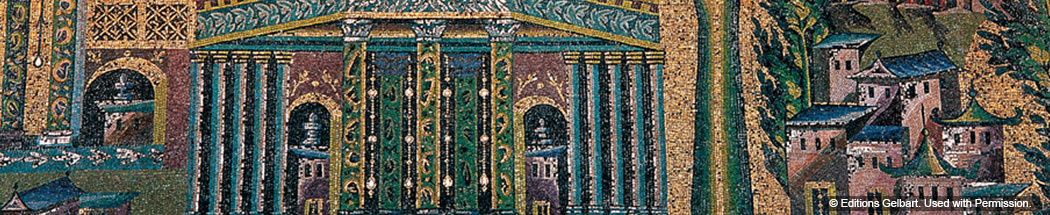

They kept us in the kitchen. Fortunately there was a tiny toilet and a servant’s room adjoining the kitchen. My mother and I lay down on the narrow bed, and covered ourselves with our house-coats. We removed the mattress from the bed and laid it on the floor. My father, who was 69 years old, slept on that mattress, covered only by a blanket. A sweater was folded over and served as a makeshift pillow. My elderly father lay on the floor while those robust young people slept in our beds and transformed the front of our beautiful apartment into a sieve. Beirut’s balconies are like smiles on its buildings. Beirutis take special care of their balconies, filling them with fragrant plants and decorating them with colorful tents and wrought iron furniture. They call them balcon - plural balakeen - or barandas, a deformation of the spanish veranda, the place from which one sees…

The gun-fire continued incessantly from all sides, and the bullets flew by or landed with a characteristic zipping sound, ruining the balcony and causing us to seek refuge in the small room often.

On the fourth day, the fighting was particularly severe. We heard the armed men leaving our apartment and climbing up to the roof to see if they could better target the street parallel to ours.

It was at that moment that I decided to leave our makeshift prison and head to my parents’ bedroom. From the door I was surprised to catch a glimpse of a fighter on the balcony, crouching behind the jasmine tree. Strangely, his handgun was lying on my mother’s bedside table, on top of her book, just next to her reading glasses and the small icon of the Virgin.

I went over and picked up the gun. It was heavier than it looked. I could hear the bullets whistling all around, and hitting the single wall that separated the bedroom from the balcony. I leaned against the wall and realized I was trembling. All I could hear was the sustained firing and the bullets flying everywhere. I held the gun in both hands, and imagined that I raised it, aimed and shot. I felt I was violently pushed back. I saw the man turn sharply toward me. I saw his green eyes. I felt the heat of the heavy gun and saw the man collapse. But I couldn’t do it.

I let go of the alien object and rushed back to the kitchen. My mother sat on the cot, my father’s arm around her. I sat next to them.

An hour later a cease-fire was declared. The armed men left and we were left to repair the damage of their visit to our balcony and our lives.